The Fifth International Conference on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Invented Languages, Omentielva Lempea, is inviting participation in an Elvish Haiku Contest open to entries in either Quenya or Sindarin. The deadline for entries is July 31, 2013. So if Elvish linguistics are your thing, you have a couple of weeks to come up with a masterpiece worthy of Matsuo Basho! Continue reading “Omentielva Lempea elvish haiku contest”

The Fifth International Conference on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Invented Languages, Omentielva Lempea, is inviting participation in an Elvish Haiku Contest open to entries in either Quenya or Sindarin. The deadline for entries is July 31, 2013. So if Elvish linguistics are your thing, you have a couple of weeks to come up with a masterpiece worthy of Matsuo Basho! Continue reading “Omentielva Lempea elvish haiku contest”

Category: Languages

A version of this article was originally published in FAMOUS MONSTERS of FILMLAND: the enduring Sci-Fi/Horror/Fantasy magazine adored by fans since 1958, created by the wonderful Forrest J. Ackerman (who was coincidentally the first agent to approach Professor Tolkien about filming an adaptation of LOTR while he was alive).

The House That Bilbo Built: Tolkien’s Literary Legacy

by Clifford “Quickbeam” Broadway

Fans of J.R.R. Tolkien have a distinctly creative way of expressing what they like; and perhaps that is the very quality that makes them the greatest fandom to propagate a literary phenomenon. It has been said there’s Life within the words of a great book. The ultimate expression of that can be seen in the inspired individual who builds his Life from the words. Those are the types of fans who carry their love so strongly forward, into bookstores and cineplexes alike, that everyone gets swept up. Their friends and children inevitably receive the books from them when the time comes; each parent, with a knowing smile, handing the key to Middle-earth to their young ones. I sometimes wonder what Professor Tolkien would think of ‘The House That Bilbo Built:’ a wave of cultural influence and entertainment begotten by the high romantic world he invented, along with so many original languages and alphabets, such a long time ago.

Fans of J.R.R. Tolkien have a distinctly creative way of expressing what they like; and perhaps that is the very quality that makes them the greatest fandom to propagate a literary phenomenon. It has been said there’s Life within the words of a great book. The ultimate expression of that can be seen in the inspired individual who builds his Life from the words. Those are the types of fans who carry their love so strongly forward, into bookstores and cineplexes alike, that everyone gets swept up. Their friends and children inevitably receive the books from them when the time comes; each parent, with a knowing smile, handing the key to Middle-earth to their young ones. I sometimes wonder what Professor Tolkien would think of ‘The House That Bilbo Built:’ a wave of cultural influence and entertainment begotten by the high romantic world he invented, along with so many original languages and alphabets, such a long time ago.

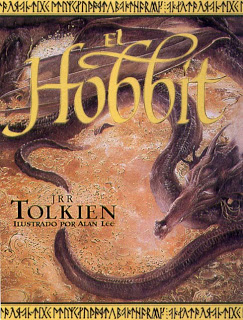

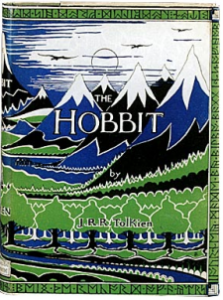

Talk about longevity! THE HOBBIT just celebrated its 75th anniversary. First published in 1937, well before the first volume of THE LORD OF THE RINGS came out (1954), the whimsical adventure of the diminutive Bilbo Baggins stands as a giant among 20th century fiction. Certainly few other books sustain the same revolving fandom over decades. I don’t believe in the least that TWILIGHT or THE HUNGER GAMES will have this measure of adoration in 75 years (but POTTER damn well might). Don’t underestimate how beloved and emulated Tolkien’s books are to a surprisingly different quilt of nations, regions, and times. The world’s appetite for Tolkien’s uniquely rich fantasy storytelling caused the actual “Fantasy” section to appear in bookstores; a niche market broadened tremendously, a statement was made to the publishing industry, and there was certainly no going back. Elves, Hobbits, Wizards, Goblins and Dragons were here to stay.

So much of my own creative life has sprung from my love of Tolkien and willingly have I swam the subculture that embraces his work.  Ringer fans are counted among the best of friends and talents I’ve had the pleasure to meet. They never cease to surprise me in their endless originality. Interviewing them for our documentary, RINGERS: LORD OF THE FANS got me really up-close; and I take joy in exploring this never-ceasing question: why are these readers so deeply connected to Bilbo’s and Frodo’s story? Why does this phenomenon keep expressing itself in the desire for cosplay, spontaneous music, academic symposiums, boisterous conventions, movie adaptations, and profuse indulgence in second breakfasts? I keep asking through all my interviews and meetings and moots; yet the answer is mercurial.

Ringer fans are counted among the best of friends and talents I’ve had the pleasure to meet. They never cease to surprise me in their endless originality. Interviewing them for our documentary, RINGERS: LORD OF THE FANS got me really up-close; and I take joy in exploring this never-ceasing question: why are these readers so deeply connected to Bilbo’s and Frodo’s story? Why does this phenomenon keep expressing itself in the desire for cosplay, spontaneous music, academic symposiums, boisterous conventions, movie adaptations, and profuse indulgence in second breakfasts? I keep asking through all my interviews and meetings and moots; yet the answer is mercurial.

And what humble, delicate beginnings for a behemoth like THE LORD OF THE RINGS! Let’s take a look at Tolkien’s remarkable publishing history, and thence pop cultural history, because it almost didn’t happen, for many reasons.

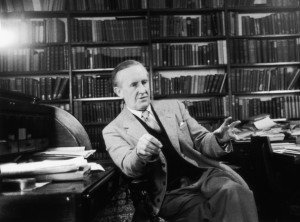

Tolkien started off developing the languages, and the foundational cosmological basis for his “secondary world,” while he was still a youngling in college, earning a degree in English Language & Literature. Then World War I arrived with death and disruption. Tolkien survived unwounded but his friends did not – he was medically discharged himself with trench fever. While on sick-leave in 1917 his wife Edith assisted him with hand-copying one of his earliest tales: “The Fall of Gondolin,” a fictional wandering that would ultimately become part of THE SILMARILLION (in fact, much of the content of THE SIL was created in Tolkien’s earlier years).

He was to become an Oxford philologist, dedicating his scholarly life to the study of languages. What better way to explore them than inventing your own! There’s a term for it: glossopoeia. As explained by TORn staff contributor Ostadan: “The word glossopoeia is a coinage derived from Greek, meaning ‘the making of tongues.’ As Tolkien explains, the creation of languages offers both intellectual and aesthetic satisfaction, but at the time he wrote, there were few such creations known to the public.”

By 1917 he was on his way to inventing Quenya and Sindarin – Elvish languages yet to be uttered by Orlando Bloom. Tolkien toyed with bits of poetry and his own slant on languages that he fancied (Finnish, Old Norse, Welsh), an effort which, oh-so-gradually over forty years, became an entire universe. He was also intent on creating a new mythology for England, which he felt lacked its own panorama of deities and “epicness” as Norway did. So THE HOBBIT was begun somewhere around 1930-31 (Tolkien recalls scribbling on a blank sheet of paper while marking examination papers, ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit’).

In 1936 Sir Stanley Unwin of Allen & Unwin Publishers got his 10-year-old son Rayner on board as the first ‘early reviewer,’ believing a child was the best judge of children’s fiction. Rayner loved it and wrote a glowing report, describing it as ‘very exciting.’ So THE HOBBIT launched in September 1937, to considerable acclaim and boffo sales.

In 1936 Sir Stanley Unwin of Allen & Unwin Publishers got his 10-year-old son Rayner on board as the first ‘early reviewer,’ believing a child was the best judge of children’s fiction. Rayner loved it and wrote a glowing report, describing it as ‘very exciting.’ So THE HOBBIT launched in September 1937, to considerable acclaim and boffo sales.

Sir Stanley quickly asked for a sequel; and the Professor sent them THE SILMARILLION, a woefully different ball of wax, with oddments of archaic manuscripts, a dense mine of data about Middle-earth’s pre-history, genealogies and somewhat biblical-style tracts that didn’t suit anyone’s taste at the publisher’s office. They wanted something with furry feet and gentle appeal.

Saying politely, “No thanks, but give us more material akin to THE HOBBIT,” they received in 1937 the first chapter Tolkien could manage – “A long expected party,” which reveled in much more hobbity sensibilities. The publishers loved what they read. But in so small an act can the hand of destiny be changed. The writing of the damn thing spiraled entirely out of control.

Tolkien felt endless pressure but wrote to Sir Stanley: “The work has escaped from my control and I have produced a monster.” This new epic was to take nearly 13 years, some say 17, during which time he held a chair at Oxford; and then, quick as you can say schnell, World War II arrived. THE LORD OF THE RINGS was finally finished in 1949. Tolkien was nigh 60 years old.

Over those years Tolkien had become quite miffed at Allen & Unwin for saying “no” to THE SILMARILLION. In 1949 he got entangled in a lengthy flirtation with Collins Publishers, hoping a new relationship would yield a home for his greatest effort.

Over those years Tolkien had become quite miffed at Allen & Unwin for saying “no” to THE SILMARILLION. In 1949 he got entangled in a lengthy flirtation with Collins Publishers, hoping a new relationship would yield a home for his greatest effort.

He eventually went back to Allen & Unwin under terms of a new agreement: they would indeed publish THE LORD OF THE RINGS, even though there was a critical paper shortage during wartime. Sir Stanley did not take on THE SILMARILLION, either, another stroke against it (after Tolkien died it finally saw print in 1977, thanks to his son Christopher’s tireless efforts).

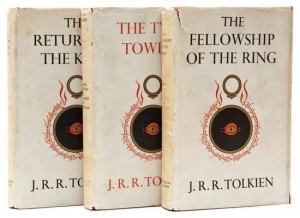

The decision to split LOTR into three volumes left the Professor rather unhappy. But he settled on the main title as THE LORD OF THE RINGS, with sub-titles for three distinct volumes (containing two “Books” each)– THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING, THE TWO TOWERS and THE RETURN OF THE KING. He would much rather it had been THE WAR OF THE RING, which he sensed would reveal much less of the actual plot, but that didn’t stick.

It was the High Summer of 1954 – Bill Haley and His Comets would rock around the clock, just as Frodo Baggins made the scene in Volume 1 of LOTR; then Volumes 2 and 3 would arrive later in 1955.

The first wave of fandom simply ate up copies regardless of its mixed reviews. Tolkien’s good friend (and fellow Inkling) C.S. Lewis came to the books’ spirited defense, declaring famously: “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.” W.H. Auden also lauded: “No fiction I have read in the last five years has given me more joy.”

The first wave of fandom simply ate up copies regardless of its mixed reviews. Tolkien’s good friend (and fellow Inkling) C.S. Lewis came to the books’ spirited defense, declaring famously: “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.” W.H. Auden also lauded: “No fiction I have read in the last five years has given me more joy.”

Steady sales and continued profits were nice, but when the American counterculture embraced THE LORD OF THE RINGS some ten years later it really skyrocketed. Over a few months time in 1966, THE LORD OF THE RINGS became a campus craze and books were seen everywhere through dormitory halls – even the University of Southern California Irvine Campus had a housing section renamed a lá Middle-earth. Causing admiration and titters alike (depending on your level of fandom) 1700 students to this day lounge in halls with such names as “Rivendell” or “Quenya.” The first and strongest wave of Western pop culture, the hippie movement, was staking its claim on how Tolkien was perceived and enjoyed by a broadly literate youth generation. Then there was the scandal of the “bootleg paperback version” of LOTR that were completely unauthorized (the guilty party being ACE Paperbacks) but that was resolved with the support of students/fans protesting booksellers who carried ACE and thus a new Ballentine edition was soon printed with Tolkien’s note on the back cover — much of this fuss we cover in greater detail in our documentary.

Then the Rock & Rollers picked up the books. An entire section of the RINGERS film covers that dynamic period where Tolkien unwittingly affected musicians of the time. Marc Bolan (of T-Rex) and David Bowie hit the underground “Middle-earth Club” on the seedy side of London. Connect the musical dots to Led Zeppelin; whose albums are rife with LOTR references and characters due to Robert Plant’s fertile affection for Tolkien’s books. I had a revealing chat with director Cameron Crowe who confessed: “Oh you’ve got to talk with my wife Nancy (Wilson of Heart), because she just loves it!” Then there was Geddy Lee (Rush), and nowadays we have Justin Timberlake – hardcore Ringers one and all.

Then the Rock & Rollers picked up the books. An entire section of the RINGERS film covers that dynamic period where Tolkien unwittingly affected musicians of the time. Marc Bolan (of T-Rex) and David Bowie hit the underground “Middle-earth Club” on the seedy side of London. Connect the musical dots to Led Zeppelin; whose albums are rife with LOTR references and characters due to Robert Plant’s fertile affection for Tolkien’s books. I had a revealing chat with director Cameron Crowe who confessed: “Oh you’ve got to talk with my wife Nancy (Wilson of Heart), because she just loves it!” Then there was Geddy Lee (Rush), and nowadays we have Justin Timberlake – hardcore Ringers one and all.

Tolkien was uncomfortable with the explosion of attention. He was a tweedy Oxford don, after all, and wanted nothing to do with the drug-addled young people tramping across his rose garden and peeping into his windows while he worked. He once called them “my deplorable cultus.” After his death in 1973, and the posthumous publication of THE SILMARILLION, the wave of pop surrounding Bilbo and Frodo became a unique beast of another color.

The holiday animation company Rankin/Bass (yes, the folks who did stop-motion Rudolph and Frosty) brought us THE HOBBIT in less than 90 minutes of Japanese-produced 2D glory in 1977. Then Ralph Bakshi rotoscoped his drop-acid take on the first half of LOTR, but he never got to make his finale. Yet the fantasy explosion of the Eighties was off to a roaring start. Tolkien fueled all this, without dispute, and up sprang authors like David Eddings, Terry Brooks, Stephen R. Donaldson, and Marion Zimmer Bradley. Someone with a polyhedral die and several pages of Middle-earthy maps invented a pen & paper game that you might vaguely recall. And you can bet your Muggle face that J.K. Rowling was devouring the Professor’s books at the time, storing it all away for future inspiration.

The holiday animation company Rankin/Bass (yes, the folks who did stop-motion Rudolph and Frosty) brought us THE HOBBIT in less than 90 minutes of Japanese-produced 2D glory in 1977. Then Ralph Bakshi rotoscoped his drop-acid take on the first half of LOTR, but he never got to make his finale. Yet the fantasy explosion of the Eighties was off to a roaring start. Tolkien fueled all this, without dispute, and up sprang authors like David Eddings, Terry Brooks, Stephen R. Donaldson, and Marion Zimmer Bradley. Someone with a polyhedral die and several pages of Middle-earthy maps invented a pen & paper game that you might vaguely recall. And you can bet your Muggle face that J.K. Rowling was devouring the Professor’s books at the time, storing it all away for future inspiration.

Enter onto the 1990’s digital stage TheOneRing.net – an online fan community affectionately known as TORn – the largest, longest-running, all-volunteer web portal unique to a single fandom. As contributors to TORn, we spend our energy reporting news, presenting special panels coast-to-coast at massive Comic-Cons and Dragon*Cons, moderating forums, chat rooms, and Facebook timelines with an endless flow of fans who collide as much as confer. We produced three gobsmacking Oscar Parties just for Ringers, one event yearly for each of Peter Jackson’s sprawling films, which were attended by the trophy-bearing cast and crew. On the year of THE RETURN OF THE KING’s 11-Oscar sweep, the Kiwi filmmakers were especially eager to greet the grassroots fan audience that so avidly showed them three years of love (and repeat ticket sales). We also produced a hellzapoppin’ Oscar event for the HOBBIT: AUJ in 2013, providing a unique atmosphere for aficionados to celebrate a shared affection for Tolkien with creators from behind the camera.

Now the newest excursion into Tolkien’s legendarium is upon us with the late 2012 release of THE HOBBIT: AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY. Not to mention the attendant merchandising and collectibles now flooding the market. Jackson and his team of film artisans surmounted terrific odds to return all the familiar players to New Zealand. The anticipation has left most fans breathless; while many purists may bemoan the stretching of an episodic 280-page children’s story into 3 extra long films. The level of involvement among fans hasn’t lessened, instead reaching a new zenith by way of shared electronic media.

Now the newest excursion into Tolkien’s legendarium is upon us with the late 2012 release of THE HOBBIT: AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY. Not to mention the attendant merchandising and collectibles now flooding the market. Jackson and his team of film artisans surmounted terrific odds to return all the familiar players to New Zealand. The anticipation has left most fans breathless; while many purists may bemoan the stretching of an episodic 280-page children’s story into 3 extra long films. The level of involvement among fans hasn’t lessened, instead reaching a new zenith by way of shared electronic media.

On our weekly live webcast aptly named “TORn Tuesday,” actors and artists ranging from Sean Astin to Peter S. Beagle join me for a merry discussion of how THE LORD OF THE RINGS has impacted their lives. They definitively illuminate how Tolkien remains so relevant. These artists have lived and breathed the magic of Middle-earth in myriad ways. Nearly 60 years later Tolkien’s masterworks have reached countless millions; and there’s a vibrant community online that supports many great events and causes, all sharing the same literary joy. I’ve never witnessed another phenomenon like it. A shared passion for the Professor’s 1200 page opus is the very liferoot of it all.

As I said, Ringer fans really do know what they like.

Much too hasty,

‘Quickbeam’

Clifford Broadway

——————————————————-

——————————————————-

Clifford Broadway, longtime contributor and webhost for TheOneRing.net, is co-author of the bestseller “The People’s Guide to J.R.R. Tolkien” (2003) and co-writer/producer of the award-winning RINGERS: LORD OF THE FANS (Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2005).

Follow us on Twitter:

TheOneRing.net @theoneringnet

Cliff Scott Broadway @Quickbeam2000

This thing went nuts with 200,000 views in 7 hours! With a busy Facebook timeline like ours at TheOneRing.net, it is always cool to see what stands out as a favorite popular post. Today’s image of Aragorn having a fun soliloquy about the day we STOP loving The Lord of the Rings became our most widely-seen and mega shared post of the year!

So why are fans so quickly drawn to a declarative statement like: “Other Fandoms may ebb and flow, but Tolkien fans are committed to these stories for life?” Quickbeam has pondered that very thing: and here is his article from this week, above

——————————————————————————————

In his first of many articles for our worldwide community, Tedoras, long-time audience participant on our TORn TUESDAY webcast brings us an illuminating discussion on something that fascinates the inner-linguist in us all: taking the very Euro-centric names and words Tolkien invented and reforming them into other languages! How do foreign-language translators deal with Tolkien’s legendarium? Read on for some keen insights! Take it away, Tedoras….

In his first of many articles for our worldwide community, Tedoras, long-time audience participant on our TORn TUESDAY webcast brings us an illuminating discussion on something that fascinates the inner-linguist in us all: taking the very Euro-centric names and words Tolkien invented and reforming them into other languages! How do foreign-language translators deal with Tolkien’s legendarium? Read on for some keen insights! Take it away, Tedoras….

————————————————————————————-

By Tedoras — special to TheOneRing.net

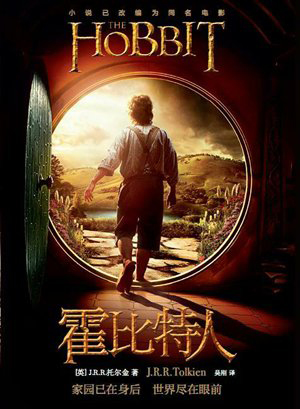

In recent years, and especially following the release of the first installment of The Hobbit films, Latin America and China have both become major sources of Tolkien fandom. While we often associate the works of Tolkien with the English-speaking world, the international nature of modern Ringerdom cannot be ignored. The Spanish and Chinese-speaking markets have undeniably helped in making An Unexpected Journey the fourteenth highest grossing film of all time. An historical challenge with Tolkien’s works, however, is how best to translate them. Whether in film or literature, translators have struggled and debate for years on how translate the names of people and places without losing the original sound and meaning that the Professor clearly intended. The process of de-anglicizing these nouns is further complicated because not only must English-language etymology be considered, but also that of Middle-earth’s many distinct tongues.

In Middle-earth, we find a strong correlation between sound and meaning that is particularly evident in the context of “soft” or “hard/harsh” names. For example, the word “Shire” conjures up visions of a distinctly British pastoral community — in essence, one notes a favorable and pleasant sense simply from reading the word. In contrast, “Dol Guldur” is composed of hard consonants and more guttural vowels which denote a rather negative air. Another popular theme is the use of alliteration; it is no mere coincidence that Bilbo Baggins lives in Bag End. As you will see, the biggest problem in translating proper nouns is deciding whether to maintain the original sound or meaning intended by the author, when often both cannot be kept.

It just so happens that Chinese and Spanish are two languages I study, so, in homage to the large Latin American and Chinese Tolkien-fan base around the world, I have decided to present some translations of proper nouns from The Hobbit. While these translations certainly highlight the many different ways Tolkien’s works can be translated, they also provide some important insight into Middle-earth (and some unintended laughs along the way).

I first present some Spanish translations of proper names.

These translations reflect an effort to keep the original meaning of a word, rather than its sound. However, because of its close relationship with English, Spanish allows for the pronunciation of many words in their original form.

Bilbo Bolsón

This is of course our favorite hobbit, Bilbo Baggins. Interesting here is the translation of the surname. In Spanish, “bolsón” is the augmentative form of “bolsa,” which literally means “bag.” A “bolsón” is simply a large bag or backpack, yet in translation it is used to convey the “bag” in Baggins.

Bardo el Arquero

Bard the Bowman is, in Spanish, literally Bard the Archer. In this case, we note a loss of alliteration in translation. It may seem trivial, but alliteration very much shapes how we view a character. The strong “b” sound in Bard’s English title provides him with a bold, confident aura. In a way, the Spanish version tries to make up for this loss by means of assonance and the repetition of the “o” in Bardo and “Arquero.”

Guille Estrujónez

Bill Huggins is one of our favorite trolls. His surname is of particular interest; in the translation, we find the Spanish word “estrujón,” literally “squeeze/press” or “bear hug.” There are two aspects to this translation: first, if we take the “bear hug” approach, then you will notice how “hug” is also present in his English surname (Huggins); and secondly, from the Spanish name one is immediately aware that this character must be strong and large.

Piedra del Arca

The Arkenstone can be interpreted many ways in Spanish. “Arca” can refer to a chest (as in of treasure) or to an ark (as in Noah’s). Either translation lends an antiquarian, more mystical nature to the stone.

In Spanish, the Shire is known rather literally as a “region” or “province”. This name was translated out of necessity, for in Spanish the “sh” sound does not typically exist. Personally, I find this name lacking of the novelty of “Shire.”

Bolsón Cerrado

The Spanish name for “Bag End” is rather odd. We find Bilbo’s surname used to represent the “Bag” in his aforementioned smial, but where one expects to find “end” there is the Spanish “cerrado” (literally “closed”). I am at a loss as to how to properly account for his translation; I will note, however, that the name flows much better as translated than if any variant of “end” had been used instead.

Montañas Nubladas

I find the Spanish name for the Misty Mountains very descriptive. Of note here is “nubladas” (literally, “cloudy/overcast”, from “nube” cloud). While “misty” and “cloudy” both denote mystery, the Spanish name is particularly foreboding; the verb “nublar” means “to darken/to cloud” and has a negative and ominous connotation in Spanish. This is of course an apt warning of the Misty Mountains.

Lago Largo

The Spanish version of the “Long Lake” is very evocative of its English translation. Both exhibit an alliterative nature and are composed of two one-syllable words. This is, perhaps, exemplary of an ideal translation, if ever there were such a thing, as neither an ounce of meaning nor sound is lost.

————————————————————————————–

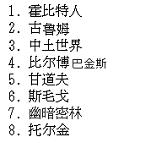

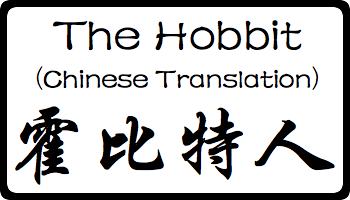

Next I present some Chinese translations of proper names.

Before continuing, however, I must note a few important characteristics of the Chinese language for those who have no experience with it. Unlike Spanish, Chinese is much more concerned with the preservation of sound. The Chinese have a long tradition of translating words such that they are phonetically similar to their native language-form. Here are two examples: first, the Chinese name for Germany is deguo (de, because of the German Deutschland, and guo meaning “country/nation”). While the character de has literal meaning (“virtues” or “ethics”), in this context it is used simply because it sounds like the “de” in Deutschland. Another example is the translation of the English name Michael; the Chinese form, maike, literally means something along the lines of “overcome wheat”. Yet, again, the Chinese in this instance forgo meaning in favor of sound. Thus, as you will see, the majority of translations involve preserving sound in Chinese. Yet looking at what potential literal translations of the names yield is a rather funny and interesting task.

This is the Chinese form of “hobbit.” It can literally be translated as “quickly compare special people.” This name, oddly enough, recognizes one truth: the unique and special nature of hobbits. Whether conveyance of this meaning was intended or not by the translator, I am not sure, though.

#2 (gu lu mu)

As you might have guessed, this is Gollum in Chinese. The literal meaning of this name is very odd: it can be translated as “nanny guru.” It does imply Gollum is old (which is true) and beholding of some secret knowledge, as a guru is (also, perhaps, true).

#3 (zhong tu shi jie)

The Chinese name for Middle-earth is an example where meaning is carried over sound. It literally means “middle earth/soil world”. However, another translation of “zhong1 tu3” is “Sino-Turkish,” though, of course, that is not the intended meaning.

#4 (bierbo bajinsi)

This is Bilbo Baggins—and a very difficult name to translate, too. The first name cannot really be translated at all. However, the surname is quite interesting; one translation could be “long for gold” which, although perhaps not applicable to Bilbo himself, is a rather pertinent note on the story as a whole.

#5 (gan dao fu)

As it sounds, this is Gandalf. The translation I like most for his name is “willing path man,” for, as we know, Gandalf is an instinctive wanderer; they do call him The Grey Pilgrim, after all.

#6 (si mao ge)

Smaug’s name is also very apt for his character. I translate this name as “careless spear,” which reflects his wantonly destructive nature.

#7 (you an mi lin)

The Chinese form of Mirkwood is another rare instance where meaning is favored over sound. This name literally means “gloomy jungle.” The dark and ominous connotation of the Chinese form is, in my opinion, much more powerfully negative than even the original English.

Lastly, I decided to include Tolkien’s Chinese name because it is oddly appropriate for the Professor. The name can be translated as “entrusting you with gold,” which I interpret in two ways: first, this can be seen as a reference to The One Ring, and, second, it can refer to Tolkien’s gift of his writings to us (his literary “gold,” if you will). Again, any intent on the part of the translator is impossible to know.

————————————————————————————

…. stay tuned for more from Tedoras ….

Join us every Tuesday for more engaging conversation with live chatters around the world who join our innovative broadcast TORn TUESDAY, featuring interviews with Tolkien/Fantasy luminaries, authors, and artists — many of whom are Ringer fans just like us! Every Tuesday at 5:00PM Pacific Time

Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew delved into the Two Towers chapter Treebeard. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. It’s a bit choppy to start but bear with it — my fault for still being half asleep when we kicked off.

Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew delved into the Two Towers chapter Treebeard. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. It’s a bit choppy to start but bear with it — my fault for still being half asleep when we kicked off.

Also, TORn regular Puma linked this excellent Youtube video of JRR Tolkien reading from the chapter when the Ents come from Entmoot to march on Isengard. Continue reading “Hall of Fire log: Treebeard”

A little earlier, Hall of Fire regulars and guests concluded a lively discussion about The Uruk-hai, the chapter of The Two Towers where Merry and Pippin escape from the clutches of the orcs. For those who missed it, here’s a log to peruse.

A little earlier, Hall of Fire regulars and guests concluded a lively discussion about The Uruk-hai, the chapter of The Two Towers where Merry and Pippin escape from the clutches of the orcs. For those who missed it, here’s a log to peruse.

Next weekend, we’ll be discussing the second of the three great unions of elves and humans: Idril and Tuor. Continue reading “Log of Hall of Fire’s Uruk-hai chat”

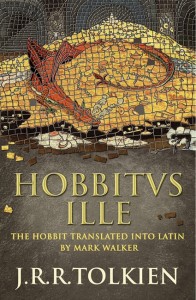

The review copy of Hobbitus Ille by Mark Walker is a beautifully presented hardcover edition with art and interior maps in the style of early English copies and is provided by Harper Collins.

The review copy of Hobbitus Ille by Mark Walker is a beautifully presented hardcover edition with art and interior maps in the style of early English copies and is provided by Harper Collins.

Walker has taken up a very brave challenge in providing us with the first Latin translation of Tolkien’s The Hobbit. His intent was to provide as direct a translation of Tolkien’s own words as possible and the end result is a complete and unabridged volume where even the poetry is in Latin. This direct translation is not the hallmark of the best translations, nor is it the Classical Latin of Caesar and Cicero. Continue reading “Reviewed: Hobbitus Ille”