Barliman’s Chat Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew examined the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. Continue reading “Hall of Fire chat log: The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen”

Barliman’s Chat Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew examined the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. Continue reading “Hall of Fire chat log: The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen”

Category: Green Books

Most people think Frodo is the true hero of The Lord of the Rings. To put it another way: It is accepted by nearly all readers that the novel is about Frodo. It’s his quest, his burden, he’s the focus. The little blurbs in magazines that are designed for the non-initiate read like this: “The story of a hobbit, Frodo Baggins, who is sent to destroy an evil Ring of power…” Sound like a good pitch? Not quite.

Most people think Frodo is the true hero of The Lord of the Rings. To put it another way: It is accepted by nearly all readers that the novel is about Frodo. It’s his quest, his burden, he’s the focus. The little blurbs in magazines that are designed for the non-initiate read like this: “The story of a hobbit, Frodo Baggins, who is sent to destroy an evil Ring of power…” Sound like a good pitch? Not quite.

The main character is really Samwise Gamgee, though you may not know it. I’m telling you now, it’s all about Sam.

You can safely argue Frodo Baggins should be the centerpoint of the tale. In The Hobbit Bilbo had the limelight for an entire book, and no one came close to grandstanding him (except maybe Smaug). Seems like Tolkien intended to chronicle the history of the Baggins family; first through Bilbo’s adventures–then with Frodo inheriting more adventures than he bargained for.

So it is a real pleasure to help publicize events like the 3rd Conference on Middle-earth and its Part 2 scheduled for 2014 in Westford, MA. The word is getting out now to declare that the conference is currently accepting papers. Below is the full press release with links, some of which show how many decades back the event reaches:

The 3rd Conference On Middle-earth, Part 2, to be held March 28 – 30, 2014

in Westford, MA, USA, is currently soliciting papers, presentations, paper proposals, and panel proposals from persons with scholarly interest in any aspect of the worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien.

in Westford, MA, USA, is currently soliciting papers, presentations, paper proposals, and panel proposals from persons with scholarly interest in any aspect of the worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Suggested topics are: J.R.R. Tolkien’s works, influences on Tolkien, other works based on Tolkien’s writing, criticism, teaching Tolkien in the classroom, the books’ impact on oneself and/or the world, the films and the film industry, the music, the art, the fannish side of this universe and its impact, and anything you can imagine on topic. For examples of previous papers and panels, see the programming for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd conferences: 1st Conference, 2nd Conference, and 3rd Conference.

A few areas of interest are:

• The languages of Middle Earth: how Old English (including Anglo-Saxon riddles), the Eddas, etc. influenced TLOTR.

• Elements of northern European myths that appear in TLOTR.

• The impact of World War I on Tolkien and his writing.

• The impact of The Hobbit and TLOTR on 1960s and 1970s popular music.

• Artistic visions of Middle-earth.

• The astronomy of Middle-earth. [For example, when is Durin’s Day?]

• The geography of Middle-earth.

• The geology of Middle-earth.

• The flora and fauna of Middle-earth.

• The clothing of Middle-earth both from the books and the films.

• The food of Middle-earth.

• The poetry and songs of Middle-earth.

Only members of the 3rd Conference On Middle Earth, Part 2, will be able to present and participate. Once papers and proposals have been accepted, the presenter/panelist will need to join the conference (the sooner the better, before rates go up), if they are not already members. If an author cannot be present, then arrangements can be made for a third party to read the paper. However, as indicated, the authors must be members of The 3rd Conference On Middle-earth, Part 2.

Only members of the 3rd Conference On Middle Earth, Part 2, will be able to present and participate. Once papers and proposals have been accepted, the presenter/panelist will need to join the conference (the sooner the better, before rates go up), if they are not already members. If an author cannot be present, then arrangements can be made for a third party to read the paper. However, as indicated, the authors must be members of The 3rd Conference On Middle-earth, Part 2.

Paper Proposal: Please email a 250-word abstract including the presentation title, your name, e-mail address, your mailing address and phone number, or alternately a second e-mail address. The maximum reading time for the finished paper is 30 minutes, roughly 2000 words, though it may be less. We will confirm receipt of proposal by e-mail.

Panel Proposal: Please email the panel name and a 250-word abstract. Please include the panel title, the panel chair (who may be one of the presenters), e-mail address, the mailing address and phone number, or alternately a second e-mail address of each presenter. The receipt of proposal will be confirmed by e-mail.

Submit your proposal to: programming@3rdcome.org.

Deadline for Submissions: You may submit a proposal up through Tuesday, 31 December 2013. Participation is limited, so submissions may close early—so it’s best to get a proposal in sooner rather than later.

NOTE: Confirmation of receipt of submissions does not guarantee acceptance for presentation.

Check out http://www.3rdcome.org for more information on the conference.

Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew delved into the Two Towers chapter the White Rider. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. Continue reading “Hall of Fire chat log: The White Rider”

Last weekend, the Hall of Fire crew delved into the Two Towers chapter the White Rider. Belatedly, for those who couldn’t attend, here’s a log. Continue reading “Hall of Fire chat log: The White Rider”

How?

Well, we also saw Smaug’s head buried in that selfsame pile. So the size of the coins gives us a basis for comparison. Continue reading “Analysis: just how big is Jackson’s Smaug?”

It is one of the first things you learn in the craft of writing. Mediocre dialogue is instantly forgotten–but brilliant dialogue lives forever in the mouth of your audience.

It is one of the first things you learn in the craft of writing. Mediocre dialogue is instantly forgotten–but brilliant dialogue lives forever in the mouth of your audience.

You know those finely crafted little moments you always remember from a movie or play? Even if you don’t see the performers again the brightest or funniest quips will linger on. The best movie dialogue has a way of becoming oft-heard bon mots relished among water cooler conversation.

The same goes for literature but often in broader measure. The most impressive wordplay remains within your psyche long after you put the book down. When the rubber meets the road, it’s how a great writer is elevated above the ordinary herds.

Indeed one of the first things you learn about J.R.R. Tolkien is that his work is ripe with just such powerful language. His wonderful ability to play with tone, color, and emotion made it easy for me to select the following from The Lord of the Rings. These are my favorite one-liners (or two-liners), that stand out as having a striking impact. Consider this collection a literary sampler akin to “Tolkien’s Greatest Hits.”

Lord knows that the Professor himself would frown upon the idea, yet I present them playfully and respectfully. Whenever I read and encounter these moments I am forever impressed with intensity, humor, or remembrance.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Most bittersweet line:

Most bittersweet line:

“I have quite finished, Sam,” said Frodo. “The last pages are for you.”

Best exclamation of joy:

“Ass! Fool! Thrice worthy and beloved Barliman!”

Most perfect description of beauty:

Young she was and yet not so. The braids of her dark hair were touched by no frost; her white arms and clear face were flawless and smooth, and the light of stars was in her bright eyes, grey as a cloudless night; yet queenly she looked, and thought and knowledge were in her glance, as of one who has known many things that the years bring.

Most poetic description of the weather:

The weather was grey and overcast, with wind from the East, but as evening drew into night the sky away westward cleared, and pools of faint light, yellow and pale green, opened under the grey shores of cloud. There the white rind of the new Moon could be seen glimmering in the remote lakes.

Most shocking moment:

Most shocking moment:

But even as it fell it swung its whip, and the thongs lashed and curled about the wizard’s knees, dragging him to the brink. He staggered and fell, grasped vainly at the stone, and slid into the abyss.

Most gruesome encounter:

Then Pippin stabbed upwards, and the written blade of Westernesse pierced through the hide and went deep into the vitals of the troll, and his black blood came gushing out.

Most colorful analogy:

“Troubles follow you like crows, and ever the oftener the worse.”

Best example of friendly competition:

“Forty-two, Master Legolas!” he cried.

Most powerful moment of rage:

Then he charged. No onslaught more fierce was ever seen in the savage world of beasts, where some desperate small creature armed with little teeth, alone, will spring upon a tower of horn and hide that stands above its fallen mate.

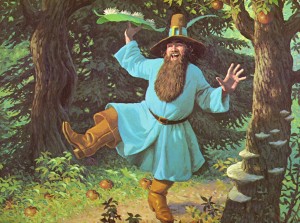

Best invitation to dinner:

Best invitation to dinner:

“You shall come home with me! The table is all laden with yellow cream, honeycomb, and white bread and butter.”

Wittiest rejoinder:

Saruman- “For I am Saruman the Wise, Saruman Ring-maker, Saruman of Many Colors!”

Gandalf- “I liked white better.”

Spookiest moment:

Farmer Cotton found Frodo lying on his bed; he was clutching a white gem that hung on a chain about his neck and he seemed half in a dream. “It is gone forever,” he said, “and now all is dark and empty.”

Most gothic description of evil:

Paler indeed than the moon ailing in some slow eclipse was the light of it now, wavering and blowing like a noisome exhalation of decay, a corpse-light, a light that illuminated nothing.

Most shrewd political advice:

Most shrewd political advice:

“He uses others as his weapons. So do all great lords, if they are wise, Master Halfling.”

Single best piece of advice:

“Do not meddle in the affairs of Wizards, for they are subtle and quick to anger.”

Single funniest line:

“…What’s taters, precious, eh, what’s taters?”

Funniest exchange between two characters:

Éomer- “…For there are certain rash words concerning the Lady in the Golden Wood that lie still between us. And now I have seen her with my eyes.”

Gimli- “Well, lord, and what say you now?”

Éomer- “Alas! I will not say that she is the fairest lady that lives.”

Gimli- “Then I must go for my axe.”

Most beautiful dream sequence:

Most beautiful dream sequence:

As he fell slowly into sleep, Pippin had a strange feeling: he and Gandalf were still as stone, seated upon the statue of a running horse, while the world rolled away beneath his feet with a great noise of wind.

Most enigmatic historical allusion:

“Fair was she who long ago wore this on her shoulder. Goldberry shall wear it now, and we will not forget her!”

Strongest statement of gender equality:

“In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen.”

Most romantic kiss:

And he took her in his arms and kissed her under the sunlit sky, and he cared not that they stood high upon the walls in the sight of many.

Most exciting call of alarm:

AWAKE! FEAR! FIRE! FOES! AWAKE!

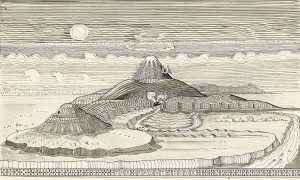

Most intimidating description of geography:

Most intimidating description of geography:

Ever and anon the furnaces far below its ashen cone would grow hot and with a great surging and throbbing pour forth rivers of molten rock from chasms in its sides. Some would flow blazing towards Barad-dûr down great channels; some would wind their way into the stony plain, until they cooled and lay like twisted dragon-shapes vomited from the tormented earth.

Most beautiful sunset:

But in front a thin veil of water was hung, so near that Frodo could have put an outstretched arm into it. It faced westward. The level shafts of the setting sun behind beat upon it, and the red light was broken into many flickering beams of ever-changing colour. It was as if they stood at the window of some elven-tower, curtained with threaded jewels of silver and gold, and ruby, sapphire and amethyst, all kindled with an unconsuming fire.

Most insidious falsehood:

“Our friendship would profit us both alike. Much we could still accomplish together, to heal the disorders of the world.”

Most spectacular moment of destruction:

Towers fell and mountains slid; walls crumbled and melted, crashing down; vast spires of smoke and spouting steams went billowing up, up, until they toppled like an overwhelming wave, and its wild crest curled and came foaming down upon the land.

Most moving speech on the battlefield:

Most moving speech on the battlefield:

“But no living man am I! You look upon a woman. Éowyn I am, Éomund’s daughter. You stand between me and my lord and kin. Begone, if you be not deathless! For living or dark undead, I will smite you if you touch him.”

Most Shakespearean dialogue:

“Stir not the bitterness in the cup that I mixed for myself,” said Denethor. “Have I not tasted it now many nights upon my tongue, foreboding that worse lay yet in the dregs?”

Most wonderful hobbit irony:

Then there was Lobelia. …and there was such clapping and cheering when she appeared, leaning on Frodo’s arm but still clutching her umbrella, that she was quite touched, and drove away in tears. She had never in her life been popular before.

Two moments that surely inspired the 60’s hippie counter-culture:

Two moments that surely inspired the 60’s hippie counter-culture:

1. “Cast off these cold rags! Run naked on the grass, while Tom goes a-hunting!” … The hobbits ran about for a while on the grass, as he told them.

and

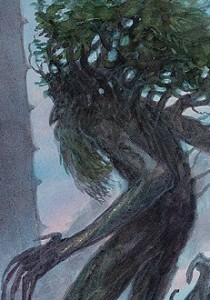

2. All that day they walked about in the woods with him, singing, and laughing; for Quickbeam often laughed. … Whenever he saw a rowan-tree he halted a while with his arms stretched out, and sang, and swayed as he sang.

Passage of utmost triumphant rapture:

And he sang to them, now in the Elven-tongue, now in the speech of the West, until their hearts, wounded with sweet words, overflowed, and their joy was like swords, and they passed in thought out to regions where pain and delight flow together and tears are the very wine of blessedness.

Line that always, always makes me weep uncontrollably:

There still he stood far into the night, hearing only the sigh and murmur of the waves on the shores of Middle-earth, and the sound of them sank deep into his heart.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Many of you certainly have your own take on what qualifies as the “most humorous,” “most shocking,” etc., and that’s fine too. This pursuit is a matter of taste, perhaps, but you cannot deny the foundation: Professor Tolkien showed his passion on every page, with every turn of phrase. Of his labors he wrote in a 1950 letter to Milton Waldman:

… It was begun in 1936, and every part has been written many times. Hardly a word in its 600,000 or more has been unconsidered. And the placing, size, style, and contribution to the whole of all the features, incidents, and chapters has been laboriously pondered.

No better insight can be given towards understanding the perfection of his tastes in authorship. Here is the major facet that most assuredly elevates him and his body of work. We, his eager readership, are indeed blessed with his remarkable and thoroughly romantic word craft.

Much too hasty,

Quickbeam

———————————————————————-

Follow Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway on Twitter: @quickbeam2000

———————————————————————-

This article was first published on August 8th 2000 in Green Books. In an effort to introduce new Tolkien fans to our nearly 14 years of archived content, we will be publishing articles like this on a regular basis. We hope you enjoy it!