Once again our friend Eirik Bull shares with us their exclusive interview, this time Eirik sat down to chat with Sir Richard Taylor of Weta Workshop. We think you will enjoy the journey they take, as they cover the early years of Weta, the making of the The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, Gollum, and much much more.

Once again our friend Eirik Bull shares with us their exclusive interview, this time Eirik sat down to chat with Sir Richard Taylor of Weta Workshop. We think you will enjoy the journey they take, as they cover the early years of Weta, the making of the The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, Gollum, and much much more.

How does one create a world? Do you start from scratch and proceed meticulously, one step at a time? Or does it usually come as a burst of inspiration, where everything happens all at once? Where does this creativity come from? Is it innate, or can it be learned? Can anyone do it, or is it a kind of everyday magic reserved for the chosen few?

More than two decades ago, I found myself in the vast cinema hall at the Colosseum in Oslo, Norway, watching The Fellowship of the Ring for the first time. Little did I know this film would be the first of three to become my all-time favorites. They would literally change my life.

What struck me most profoundly was the seamless blend of what felt utterly “real” and unmistakably “magical”. It was as if a tangible, enchanting form of sorcery had been wielded to bring J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth to life on the big screen. And more often than not, when delving deeper into creations woven from formulas and magic, you will discover the true wizard at their core.

In December 2022, I met the wizard I’m introducing today: Sir Richard Taylor, the esteemed (and quite nerdy) owner of Wētā Workshop in New Zealand. “Just call me Richard,” he insists, shrugging off formalities, including his knighthood. This laid-back demeanor is humorously showcased by a massive mural outside the wonderful public attraction “Wētā Workshop Unleashed” in Auckland, where he’s hilariously depicted in his underwear, astride a rocket Dr. Strangelove-style, and strumming a bass guitar. This knight remains refreshingly unpretentious.

I have some pictures of the mural I took with my mobile phone while visiting Wētā Workshop Unleashed. They asked me not to share them online. The mural is so unique, so magnificently strange, that it really needs to be experienced with one’s own eyes. And you know what? I completely agree!

So, in December, when I visited Wētā Workshop in Wellington, New Zealand, I had a chat with Richard in his office. Science fiction and fantasy figures were everywhere, and the walls were adorned with concept drawings – some discarded, while others had already made their way into major blockbusters or would do so in the future. Next to Richard, there was a chair where a small dog sat. Wētā Workshop is a “dog-friendly” workplace where 35 of man’s best friend roam freely in the corridors.

The interview below is actually based on two interviews I’ve had with Richard. The first was on Zoom a year or so before I visited New Zealand, and the next was in the meeting I had with him at the Wētā Workshop in December of 2022. I’ve used one as a base and added details from the other to create what I hope you will find to be an insightful and entertaining deep dive into this wizard’s creative mind.

What role did Tolkien’s books have in your childhood and growing up?

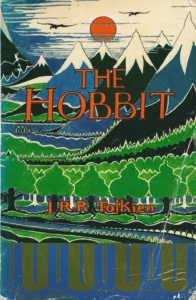

Well, The Hobbit was the book that truly impacted me during my early years, when I was around 10-11 years old. At that time, I wasn’t a strong reader—I struggled with reading quite a bit. So, the epic scale of The Lord of the Rings was a bit too challenging for my reading level. My journey into Middle-earth began with The Hobbit, and it resonated with me profoundly.

Well, The Hobbit was the book that truly impacted me during my early years, when I was around 10-11 years old. At that time, I wasn’t a strong reader—I struggled with reading quite a bit. So, the epic scale of The Lord of the Rings was a bit too challenging for my reading level. My journey into Middle-earth began with The Hobbit, and it resonated with me profoundly.

Interestingly, around the same time, I bought a print of The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch for two dollars at a library’s closing-down sale. I hung it above my bed. Until then, I hadn’t fully grasped the concept that a fantasy world could exist parallel to our real one.

Growing up on a farm, life was very practical. My father was an aircraft engineer, and my mother was a science teacher. Our daily life was straightforward, lacking a sense of the fantastical. So, the combination of Bosch’s work—gazing into that painting and discovering the fantastical, demonic world he depicted—and reading Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which invokes similar conceptual ideas, especially when considering the darker aspects of Middle-earth, opened my eyes. I of course had other creative influences as well. The comic series 2000AD, the TV series, Thunderbirds Are Go, A wonderful book on Chinese sculpture that inspired me to sculpt, a copy of Faeries by Brian Froud and Alan Lee – and various other things that I found inspired me.

Because of this, I began to realize that my mind could wander into a much broader spectrum of thought. This realization catalyzed and energized my understanding of the fantastical.

What did it mean for you to be able to work on a project like The Lord of the Rings?

It’s now a well-known story. Peter called us up and said, “You’d better come around. Bring Tania and the guys. Grab some fish and chips, and don’t forget the Coca-Cola. I’ve got something to tell you.” So, we went to his house, and the “guys” were the five concept artists working with us at the time. We had been working on King Kong in 1996, which, unfortunately, didn’t go ahead, and Peter quickly needed a new project. He traveled overseas, intending to come back with something new. When we arrived at his house (after grabbing fish and chips from a shop just two minutes up the road here in Miramar, Wellington), Tania, myself, and the guys (two still working here today), people like Daniel Falconer, Jamie Beswarick, sat on the carpet, and Peter announced we were going to make two films of The Lord of the Rings with Miramax.

I likened it to being teetering at the edge of a precipice. The weight of expectation at that moment was extraordinary. You’re aware of the literature’s pedigree and its importance to hundreds of millions of people. What we were about to do had to respect Tolkien’s literature while fulfilling the preconceived notions of Middle-earth held by its readers. Interestingly, we did C.S. Lewis’ work right after Tolkien’s, as there’s a notable comparison. Tolkien’s writing is incredibly visual. He could draw what he wrote and often did. His descriptions are rich in visual imagery. In contrast, C.S. Lewis, for example, in The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, has a battle that lasts just five or six pages without the same depth of description, necessitating a more inventive design to visualize the world. With Middle-earth, we could constantly refer to Tolkien’s writing, almost like a blueprint.

I likened it to being teetering at the edge of a precipice. The weight of expectation at that moment was extraordinary. You’re aware of the literature’s pedigree and its importance to hundreds of millions of people. What we were about to do had to respect Tolkien’s literature while fulfilling the preconceived notions of Middle-earth held by its readers. Interestingly, we did C.S. Lewis’ work right after Tolkien’s, as there’s a notable comparison. Tolkien’s writing is incredibly visual. He could draw what he wrote and often did. His descriptions are rich in visual imagery. In contrast, C.S. Lewis, for example, in The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, has a battle that lasts just five or six pages without the same depth of description, necessitating a more inventive design to visualize the world. With Middle-earth, we could constantly refer to Tolkien’s writing, almost like a blueprint.

However, this meant that the audience would have strong preconceived images of the world. That came with significant expectations. We decided to focus on conceptual design for armour, weapons, creatures, miniatures, special makeup effects, and prosthetics. Five departments – a large task for a small group. Initially, we had 36 people, and ultimately of the 158 people we hired, only about 1/8 of them were experienced in working in film or TV. The rest trained from scratch. Seven and a half years later, they were all experts in their craft.

So, you either step back from the precipice, thinking it’s too hard, or you step over and free-fall. What catches you is the collaboration, first and foremost with your friends and colleagues, no one more so than the director, Peter Jackson. His core understanding of the literature, his faith in us all, his faith and grasp of digital technology, and his willingness to let us work independently were vital. But also, his recognition that we needed the help of top talent for the concept design of the films – and brought in Alan Lee and John Howe. Their inspiration and talent was invaluable. In the seven and a half years, I never doubted that this was the best thing for me and my colleagues to be doing. Despite the challenges, it was always enjoyable. The joy of what we were doing, with whom, and for what reason outweighed any difficulties.

Being asked to work on it meant a phenomenal amount to me. And for Wētā Workshop to be entrusted with several departments was incredibly impactful and very special.

How did Wētā Workshop start? Can you talk about some of the early productions with Peter Jackson?

We began our journey a few years before meeting Peter. My wife and I ran a small FX shop from our flat’s back room named RT Effects (Richard and Tania’s Effects), mainly servicing local TV commercials. Our big break came with a New Zealand version of Spitting Image. I sculpted all the puppets in margarine, creating around 70 in total. During this time, Peter, unbeknownst to us, was completing Bad Taste, his first movie.

We were introduced to Peter through a mutual friend. He had seen our satirical puppet show on television and seemed surprised to find someone else in the country, let alone our city, doing this kind of work. We quickly became good friends and spent a lot of time together. We didn’t work on Bad Taste, unfortunately. I wish we had known him a year earlier, as I would have loved to contribute. However, he invited us to work on the initial Braindead. Tania and I handled the construction of models, miniatures, and props. But about 12 weeks in, the project fell through. Peter, ever resourceful, secured funding for a smaller movie, Meet the Feebles. Under the guidance of Cameron Chittock, a talented New Zealand creator and our mutual friend with Peter, we made puppets for six months. During filming, I built all the miniatures, and Tania managed the puppet wrangling.

Then we returned to Braindead. This time, with half the original budget, Peter entrusted Tania and me with the effects instead of the Australian workshop initially planned. Working on such an intense and joyful project was an incredible experience. In those early years, we worked on Hercules and Xena, along with numerous TV commercials. During Heavenly Creatures, we handled physical puppetry, suit work, and miniatures. Peter, eager to adopt digital technology, wanted 14 digital effect shots for this Kiwi film. Pooling our financial resources, we all bought our first machine—a Silicon Graphics computer, the first in New Zealand and possibly the southern hemisphere.

This computer was the cornerstone for establishing Wētā Digital. It enabled us to work on Contact and The Frighteners as we expanded our digital effects capabilities. Meanwhile, Tania and I remained focused on the physical effects side of our company. And from there, the rest is history—The Lord of the Rings, King Kong, and many more. Today, we no longer have ownership in Wētā Digital, having chosen to concentrate entirely on the practical FX aspects of our business.

Why do you think New Zealand makes such a great Middle-earth? Is there something about the country’s identity you can point to?

It is, and I will speak to that. But I think first and fundamentally, it is always about the individual. It’s about the filmmaker. Middle-earth was created in New Zealand because of Peter Jackson, because of his indomitable spirit and his extraordinary filmmaking capabilities. Remember, this is a person who had made, a 14 million dollar movie in The Frighteners and then jumped to a 360 million dollar movie trilogy with The Lord of the Rings. And I don’t think at any moment Peter hesitated in his confidence that he could actually do The Lord of the Rings. Maybe there were others, producers and studio execs, that were less confident. But I never saw Peter falter in his confidence.

So certain was he in his strategy on how he was going to make these films. But that’s not to take anything away from the incredible film industry that exists here. With a limited number of foreign experts (he brought in the First Assistant Director and Director of Photography from Australia, amongst others from around the world), it was wonderful, as it was crewed predominantly by New Zealanders.

I’ve suggested in the past – that just a director didn’t make the movie. It wasn’t made by just a film company or just the New Zealand film industry. Our whole country made it! Because the whole of New Zealand literally got behind the making of these movies. And there was definitely a sense of pride in the fact that, as a country, this could be made due to the huge number of extras required and the huge number of people who got involved, both directly and indirectly. The army got involved. The government got involved. The people of New Zealand got involved. It was actually a very beautiful thing for our country.

I’m sure a limited few would disagree, but I think, for the most part, it was a moment of extreme pride where our country was able to stamp our mark creatively on the world stage. Although we had a very dynamic film industry pre-The Lord of the Rings, making very beautiful films, our country’s films had not really been witnessed by a large proportion of the world’s public. And so, The Lord of the Rings was our first chance to really show the world the creative capabilities of our country, and that pride and energy certainly enhance the filmmaking process.

And then you have, of course, the people themselves. We have incredible talent in this country. Not just our cast and crew but the people who provide the services and support that we need, whether it be caterers, builders, or electricians. We have incredible service providers. We have incredible ingenuity. We have incredible inventiveness.

And all of this is being done in this relatively small corner of the world. And it just so happens that it lined up very, very nicely. There are many other places that you could have gone in the world to make these movies, that would be magnificent in their own right. But it is difficult to know whether they would have been as easy or as forgiving or as magnificently beautiful as the landscapes of New Zealand were. It is not lost on me; believe me, how blessed we were to have this incredible resource at our disposal.

Can you talk about some of the main breakthroughs, like Gollum, for example, that Wētā Workshop came up with while working on The Lord of the Rings?

I think with respect to Gollum and also with respect to some of the other digital achievements, once again, acknowledgment has to be given to the fact that Peter, as a producer and creator of the movies, made early technical decisions that required him to be immensely confident that the technology would one day deliver. When you have to leave a hole in the movie where a major character is going to exist, and you choose not to shoot an alternative take using an actor with prosthetics for a character such as Gollum, and because you are betting everything that a small team of people within your digital effects division are going to develop a hyper-real and completely plausible actor that can play besides your flesh and blood world-class performers – now that’s a massive decision.

And he did this multiple times when you think about the armies, other digital characters, and environments. Tolkien described armies of immense numbers of soldiers. And at the point we were making the movies, there was a very limited number of ways that you could have brought that to life convincingly. Obviously, you could have attempted to do what some directors have done. And it’s still prevalent in China, where you actually dress up thousands and thousands of extras. Or you composite small blocks of blue-screened extras into a scene again and again. But he knew that none of that was going to be satisfactory. So, one person with a computer and a small team around him developed the software Massive, which has now become so well-known and part of the folklore of Middle-earth.

But watching that unfold monthly, as the very first tests were rolling out of Wētā Digital, no one really knew whether this approach was going to fulfil expectations. Then, seeing libraries of motion-captured movement being put into the computer, which would then randomly draw from these movements to create authentic performances on huge battlefields to give these sweeping, dramatic scenes, was mind-boggling. It was groundbreaking and brave. Brave for Peter. Brave for the producers. And it is very brave for the digital effects artists that did the work and pulled it off.

At Wētā Workshop, we may not have been breaking massive new ground in the manner Weta Digital were, but still, for us, it was all so groundbreaking – just because of the mass production of armour and weapons, characters and creatures, miniatures and models. The quantities of prosthetics that were needed every day were staggering at times. So, we needed to come up with unique and clever techniques and iterate and invent on the fly almost daily.

The most critical thing for our company is the ability to ‘innovate new methodologies.’ If we don’t innovate, but rather, keep on using the same old techniques that we’ve always used, we won’t be cost-competitive, and we won’t be able to run multiple jobs in parallel. The way we used to do it was all 100% handcraft skills; today, over 60% of everything we make is assisted through robotic manufacturing, 3D printing, milling, laser cutting and so on. So, the ability to innovate is a very critical part of what we do.

Let’s talk about Gollum. Did you ever consider any other methods or ideas for creating this important and iconic character?

We briefly considered it. We actually took one of our designers, a guy called Chris Guise, who, at the time, was incredibly slim. And we made prosthetics for his hands and the back of his head so we could shoot over his shoulder. I think it was only ever used in one scene. At the time, this caused a bit of a realization.

It could be argued that, ultimately, you only want one reality for a film character. If you build a puppet or put an actor in makeup that you are going to use for some of your shots, the digital effects company is going to do the wide shots, the running shots, the action shots, and so on. It can become more difficult to replicate the reality you have created by physical means – which is an absolute reality since it has been filmed on set – than to create an alternate reality. Ultimately, it is often easier for the audience to buy into the one alternate reality, let’s say Gollum, a digital character driven through motion capture and incredible animation, than trying to grasp two realities: our puppet version and the digital version.

And it became very clear in those first few months that jumping between the two was going to be very hard to do. It wasn’t going to look as good as we all hoped , and it was going to be less than perfect. So, the decision very early on was to trust the fact that one day they would solve complex issues required to create a photorealistic character such as Gollum, (such as subsurface scattering) so that the super clever folks at Wētā Digital would be able to create the authenticity of Gollum.

At some point in the production, Joe Letteri joined Wētā Digital as the visual effects supervisor, and he ultimately collaborated with Gino Acevedo, a physical effects technician who had come down from the USA to work with us to do all the character paint designs in our workshop. Gino helped Joe and his team understand how to create a sense of translucent skin that looks terrific to the camera. So, in collaboration with the incredible digital artists who also worked on Gollum, there was this amazing transference of knowledge, ideas, and inspiration that went into the creation of what we saw on film.

Looking back at The Lord of the Rings trilogy now, is there a physical set piece, costume, or similar that you are especially happy with?

I’m going to give you a slightly multi-faceted answer. My favorite character that we created was Lurtz, who was played by New Zealand actor Lawrence Makoare. Ultimately, any prosthetic character you create is only as successful as the performance of the person inside the makeup. And Lawrence is one such person. Wonderfully, we have all remained friends with Lawrence. He’s a huge guy, and he has such a powerful presence. So, Lurtz was, to me, the most special character we created amongst a huge number of very special characters.

I have a great love for miniatures, and I lament the loss of miniatures from the screen industry. It’s a very rare thing today to see miniatures. I think the last time we built them was for Blade Runner 2049. It was magnificent that the director was willing to shoot miniatures. On Ghost in the Shell, we also got to build miniatures, although these were photographed and used as digital overlays for the digital environments. But at least we got to build them.

On The Lord of the Rings, we built 72 miniatures, if I can remember the number correctly. The beauty of Rivendell from Alan Lee’s drawings was one of the most extraordinary things I got to build with my friends and colleagues. Our senior model makers, Mary MacLachlan and John Baster had built that miniature along with two other people and me. You can imagine having read about it and then one day getting to build it, and you’re building it from Alan Lee’s sketches! We never did a plan for it; we just literally used his pencil and water colour sketches, and it grew from these.

That was when I really understood and appreciated Alan’s creative brilliance. As I mentioned, the very first art book I bought was the one titled Fairies by Alan Lee and Brian Froud, and this inspired me hugely. Still, it wasn’t until we built the miniatures that I really understood his ability to visualize on a near-savant level. He would do a series of seemingly disconnected drawings, but if you would wrap those drawings around a cone, they would perfectly marry up and give you a complete study of the environment.

Likewise with Minas Tirith. Alan provided a series of sketches for us to build from. For this miniature, we literally piled a whole lot of cardboard boxes together, sprayed them with urethane foam, carved them back, and then started building onto them. Never could we think that this miniature would end up going on to be exhibited in a museum, having a life well beyond the movie. If we had known, we would have built it a little better. But we were building them so cheap, so fast, that I really was of the view that the only thing that mattered was that they just needed to hold up for the filming.

The very last thing we ever built on The Lord of the Rings, five days before the film was sent off for print, was the docks from The Return of the King. It was filmed, it was edited, and it was composited into the movie in five days. I love that scene. I love the army of the dead flowing over the edge. I love the heroic moment of Aragorn leaping over the gunnel of the ship and running to shore. I think it’s because of the last-minute nature of this build that I still think so fondly of it.

And of course – the incredible inspiration that came from our creative relationship with John Howe – who taught us so much about medieval armour and weapons, the inventiveness of his creature design, the fantastical nature of his building and landscape work – all truly magnificent!!

And finally, what is your fondest memory from the whole project of making The Lord of the Rings?

Walking down the red carpet with my wife in Wellington for the premiere of the first film. The whole city had turned out, and the sense of overwhelming emotion and energy – I guess that’s probably the most impactful.

Walking down the red carpet with my wife in Wellington for the premiere of the first film. The whole city had turned out, and the sense of overwhelming emotion and energy – I guess that’s probably the most impactful.

If I rephrase the question slightly, what is the most important thing for me to get out of these movies? It is the knowledge that we were able to take a large group of people who otherwise had never had the chance to work on something like this before. Through the infrastructure of our company and, hopefully, the inspiration of the project, a group of people were empowered to achieve things that they could never have possibly imagined before we got to work on these movies.

I love thinking that young people join us and learn to make. The joy of making is often underrated today. I have a very strong view that the craftsmanship of any country is the road markers through history that define what was happening at that point in that country’s history. The loss of craftsmanship is a huge loss for our world, and I, therefore, love that we try to keep that alive through the work we do every day on films such as The Lord of the Rings.

To me, knowing that we were able to contribute to this really special trilogy of films for those seven and a half years and to engage the level of craftsmanship necessary to make our part of these movies with a group of creative technicians that came together passionately to do something special – that is what I remember, and that will always be the highlight of the project for me.