I’ve been re-reading The Children of Húrin lately in preparation for TORn’s chapter-by-chapter discussion in our chatroom. (We’re starting our discussion later today in The Hall of Fire. Feel free to join us at 6pm ET as we dive into Chapter 1.)

I’ve been re-reading The Children of Húrin lately in preparation for TORn’s chapter-by-chapter discussion in our chatroom. (We’re starting our discussion later today in The Hall of Fire. Feel free to join us at 6pm ET as we dive into Chapter 1.)

It’s been some years since I’ve read The Children of Húrin in full; I probably haven’t completed a cover-to-cover reading since the novel was first published in 2006. But it’s always interesting how revisiting a novel after a long period sometimes gives you a totally different perspective on the action.

So as I’m reading along, I’m going to try and briefly write about one new thing that strikes me each chapter.

Túrin and Sador; Turin and Brandir: a study in contrasts?

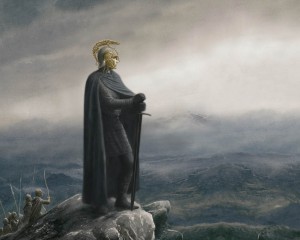

The first chapter focuses strongly on Túrin’s background — particularly his childhood in Dor-lómin and his friendship with Húrin’s household retainer, Sador.

The ur-story as related to us in The Book of Lost Tales (Turambar and the Foalókë) contains none of this detail. This suggests that Tolkien consciously added this childhood background. And realising that made me to wonder: to what purpose? What does it tell us about Túrin’s character that we cannot otherwise grasp?

Perhaps one answer lies with a character who appears towards the end of The Children of Húrin — Brandir.

Originally called Tamar Lamefoot in The Book of Lost Tales version, Brandir goes halt on one foot. Just like Sador.

Brandir, similar to Sador is “no man of war”. Yes, Sador did a stint as a guard at Eithel Sirion, but eventually decided war was not to his liking. Brandir is unable to fight, “being lamed by a leg broken in a misadventure in childhood”.

Brandir is said to love “wood rather than metal”. Sador works as a woodcutter for Húrin, and eventually is tasked to carve a chair for his lord.

The parallels cannot be coincidence. It’s almost the sort of conditions you’d see in a lab experiment to test a hypothesis.

How does our lab rat behave towards each, then?

The youthful Túrin treats Sador with courtesy, kindness and generosity. He’s the confidant that Túrin turns to after the death of his younger sister form plague. Although he gives Sador the nickname Labadal (meaning “hopafoot”), the name is not given with malice or scorn. He is even moved to give him the elven-made knife that Hurin gives him for his birthday.

Húrin soon marked that Túrin did not wear the knife, and he asked him whether his warning had made him fear it.

Then Túrin answered: ‘No; but I gave the knife to Sador the woodwright.’

‘Do you then scorn your father’s gift?’ said Morwen; and again Túrin answered: ‘No; but I love Sador, and I am sorry for him.’

Túrin doesn’t bear the same sort of affection for Brandir. That is, perhaps, to be expected. But he does show him respect: initially, at least, he heeds the Lord of Brethil’s wishes for caution.

‘The Mormegil is no more,’ said he, ‘yet have a care lest the valour of Turambar bring a like vengeance on Brethil!’

Therefore Turambar laid his black sword by, and took it no more to battle, and wielded rather the bow and the spear.

But fortune is not content to let Túrin be, and he is soon forced to take up the black sword again. The implication of the text is that in doing so, he usurps Brandir as the de facto, if not de jure, leader of the Haleth.

… he sent out men of daring as scouts far afield. For indeed, though no word was said, he now ordered things as he would, as if he were lord of Brethil, and no man heeded Brandir.

And when Dorlas indirectly scorns Brandir’s lameness and inability to take during the final war council, Túrin initially says nothing. His delayed praise for Brandir’s wisdom and healing skills seem paltry recompense for damaged reputation at the hands of one who is essentially Túrin’s minion.

And not long thereafter Túrin himself is emulating Dorlas at Cabed-en-Aras, deriding Brandir and calling him “club-foot” in front of his people not once but twice.

It’s hard to credit that the young Túrin would have acted and spoken the same — even in anger and distress.

I wonder, then, whether this is one of our clearest sights of Morgoth’s curse on Húrin and his kin. For in the youthful Túrin we see his pity and compassion. In the adult, we see how that empathy can be twisted to malice.

Hall of Fire will be discussing this and a lot more later today as we begin our chapter-by-chapter discussion (we’re doing on chapter every two weeks). If you’d like to join us, just come to our chatroom through this link at 6pm ET!