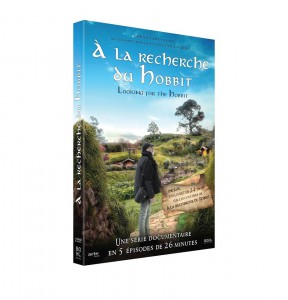

While Tolkien was a British writer, his readership and influence extend far beyond the English language. Middle-earth transcends both time and culture as we have seen again and again when having the pleasure to meet fellow fans from around the globe through both TheOneRing and Happy Hobbit. That said, sometimes it takes a little longer for Tolkien events and/or specials in other languages and countries to reach our ears. Fortunately for you, dear reader, famed Tolkien artist and scholar John Howe sent a message our way via thrush to let us know about a delightful Franco-English documentary he narrated in 2015 about the source material for Tolkien’s The Hobbit titled A la Recherche du Hobbit (Looking for the Hobbit).

You can watch the first episode of five in English below:

Looking for the Hobbit ep1 from CERIGO Films on Vimeo.

If you’re confident enough to navigate the French website (all you have to do is click on the shopping cart icon!) you can purchase a region-free English version here, and the series is available in French on DVD and streaming here (along with a preview). You can also peruse several delightful behind the scenes photos on their Facebook page.

What’s more, John Howe has taken the time to provide us with his thoughts on why, even after all this time, he was excited to contribute to yet another exploration of Tolkien.

AREN’T YOU TIRED OF TOLKIEN YET?

by John Howe

I’m often asked: Haven’t you had enough of Tolkien by now? Invariably, I reply that no, not really, that there is still so much left to explore. Inwardly, I am thinking that Tolkien must have quite enough of us, all the well-meaning, earnest individuals with no particular ties to the opus, but buzzing busily around the edges, forever finding something to exclaim about, some insight to provide, some clever observation to make. What pests we must be.

Happily, the texts remain, and even more happily, they have reminded us of the source that touched the author, and provided indirect introduction for those who wish to look a little deeper.

It’s always the same story with stories. Their attractiveness, the things that touch us deeply or in passing, similarly touched the author, or we may guess that they have. Those moments, the evidence of which we glean between the lines, are where the true interest lies: the coming together of mind and material, often centuries apart in time, to create a new story. I’ve always been fascinated by the spark that sets off creation of a work, whether literary or pictorial, and the brief illumination provided. I see the history of artistic creation as something of a landscape in the half-light of dawn or dusk, filled with fireflies; brief sparks kindled in the imagination.

In that light, Tolkien is no longer simply fantasy fiction, or, an even more severe accusation, escapist literature, but a collection of references, a thematic lexicon of fascination with things both timeless and deeply rooted in context. (We cannot truly appreciate the wicked step-mothers of fairy tale without an appreciation of the precarious position occupied by the new wife’s husband in the family household, or take into account the terrible toll of death in childbirth.) Proper appreciation of a theme means focusing equally on the theme itself, whether one leans towards Freud and Bettlelheim or prefers Jung and Von Franz, but focusing equally clearly on the storytellers themselves, their audience, and what they might have understood.

In the broader context, much fantasy literature is dismissed outright (and rightly so for the most derivative consumer literature) but the tenants of modernity in the grittiest street-corner sense roll up their eyes at any mention of the fantastical, preferring to hop on the last metro rather than walk home through the woods. Confusing context with genre is an easy way to narrow the scope of consideration, and an effective way to limit any debate.

Considered in context, each approach brings new understanding and new questions, each approach situates the wanderer a little more clearly in the world of his or her own choosing – the material world with the world of myth superimposed. In that sense, the “Haven’t you had enough of Tolkien?” question is like asking haven’t you had enough of the sea and the mountains.

Equally, we are the generations of the immobile voyage – armchair travelers with behinds firmly lodged in easy chairs, books held in front of noses (or screens). People travel for travel’s sake, or for purposes scholarly: history or ethnology, they rarely travel for fantasy. Nevertheless, fantasy is as deeply rooted in the soil as any ancient ruins we can stroll amongst. Dealing with fantasy in context can mean actually putting in a few miles and a bit of a walk. In an age of experience by proxy and the digital abolishing of distance, sometimes it is useful to go stand in a particular spot, to become someone, somewhere, at some point in time, contemplating something. This conjugation of singulars is often needed to achieve a form of plurality of appreciation, Jung’s much-misunderstood collective consciousness.

Those were the principal reason that pushed me to accept the role of hesitant narrator in “Searching for the Hobbit”, the opportunity to combine early morning starts, long cold days shooting on location and spontaneous thoughts on a theme. That, and the enviable position of the narrator: no responsibilities except keeping your wits about you. Five episodes in all, five steps closer to… well, something, with the knowledge that no matter how close you get, it all remains just out of reach.

Thoughts during the shoot in New Zealand:

http://www.john-howe.com/blog/2013/07/16/enter-frame-left/