Welcome to our latest Library feature, in which Benita J Prins discusses the belief that Tolkien characters are either totally good, or totally bad, and therefore his characterizations are two-dimensional. She shows that Tolkien did, in fact, write characters that aren’t good, but aren’t entirely bad, and they appear in all of his works.

Welcome to our latest Library feature, in which Benita J Prins discusses the belief that Tolkien characters are either totally good, or totally bad, and therefore his characterizations are two-dimensional. She shows that Tolkien did, in fact, write characters that aren’t good, but aren’t entirely bad, and they appear in all of his works.

The Greyscale

By Benita J. Prins

Tolkien is often blamed for creating black and white characters. Either they’re completely on the good side, or they’re completely on the bad side, and for this reason there are a ton of other authors who are way better at characterization that Tolkien is. When I come across assertions such as these, I find them strange and incomprehensible. Quite contrary to what these people claim, Tolkien’s stories are full of complex characters. I intend to take a few examples of such characters in the various tales of Middle-earth, including The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, and to disprove this idea.

Thorin stands out clearly from The Hobbit as someone who is on the greyscale. Whilst he is on the good side, he has quite a few flaws. He is domineering and bossy, and rude to Bilbo; he loses his temper easily; and he is greedy, obsessed with recovering the treasure stolen by Smaug. He becomes terribly angry with Bilbo when he discovers that Bilbo has given the Arkenstone to Bard, and calls the hobbit a “descendant of rats”[1], as well as threatening to kill him. As a just return for his deeds, Thorin, rather than Bilbo, is killed, in the Battle of the Five Armies, but not before he repents of his anger and apologizes to Bilbo for his words.

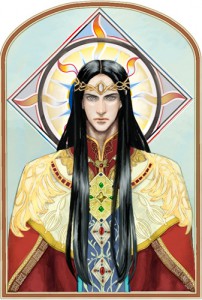

From The Silmarillion, we have several characters – Túrin, Fëanor and his sons, and Isildur. Túrin is the son of Húrin, the only survivor of one of the worst battles recounted in The Silmarillion[2]. The Dark Lord Morgoth curses Húrin’s family, and bad luck trails Túrin throughout his life. Túrin ends up killing his best friend Beleg, marrying his sister unbeknownst to either, and finally committing suicide. My use of Túrin as an instance of a grey character is admittedly slightly flawed by the fact that he was cursed, but I believe he may still serve as an illustration of my point. My next Silmarillion example is Fëanor, who was the creator of the Silmarils, the jewels from which The Silmarillion takes its title. However, Morgoth desired them greatly and successfully conspired to steal them. When this happened, Fëanor and his seven sons swore a terrible oath to search out and kill anyone else who held a Silmaril. This oath led to a great deal of strife in Middle-earth. Now Fëanor and his kin were Elves and had not been corrupted into the service of the Dark Lord, but their lust for the Silmarils led them to commit many evil deeds. Finally, we have Isildur, of whom Aragorn is the heir. Isildur was the one ultimately responsible for Sauron’s defeat at the Last Alliance battle at the end of the Second Age; after Sauron killed Isildur’s father Elendil, Isildur took his father’s broken sword and cut off Sauron’s finger which was wearing the One Ring. Isildur certainly had the chance to destroy the Ring then and there: he was on the very slopes of Mount Doom, and Elrond urged him to throw it away. Sadly, Isildur succumbed to the lure of the Ring and kept it instead. This caused not only his death, but also the deaths of many other people, most notably in the War of the Ring. These are but three cases of grey characters in The Silmarillion.

From The Silmarillion, we have several characters – Túrin, Fëanor and his sons, and Isildur. Túrin is the son of Húrin, the only survivor of one of the worst battles recounted in The Silmarillion[2]. The Dark Lord Morgoth curses Húrin’s family, and bad luck trails Túrin throughout his life. Túrin ends up killing his best friend Beleg, marrying his sister unbeknownst to either, and finally committing suicide. My use of Túrin as an instance of a grey character is admittedly slightly flawed by the fact that he was cursed, but I believe he may still serve as an illustration of my point. My next Silmarillion example is Fëanor, who was the creator of the Silmarils, the jewels from which The Silmarillion takes its title. However, Morgoth desired them greatly and successfully conspired to steal them. When this happened, Fëanor and his seven sons swore a terrible oath to search out and kill anyone else who held a Silmaril. This oath led to a great deal of strife in Middle-earth. Now Fëanor and his kin were Elves and had not been corrupted into the service of the Dark Lord, but their lust for the Silmarils led them to commit many evil deeds. Finally, we have Isildur, of whom Aragorn is the heir. Isildur was the one ultimately responsible for Sauron’s defeat at the Last Alliance battle at the end of the Second Age; after Sauron killed Isildur’s father Elendil, Isildur took his father’s broken sword and cut off Sauron’s finger which was wearing the One Ring. Isildur certainly had the chance to destroy the Ring then and there: he was on the very slopes of Mount Doom, and Elrond urged him to throw it away. Sadly, Isildur succumbed to the lure of the Ring and kept it instead. This caused not only his death, but also the deaths of many other people, most notably in the War of the Ring. These are but three cases of grey characters in The Silmarillion.

In The Lord of the Rings, I have three examples of characters who are by no means black or white: Boromir, Frodo, and Gollum. Now Boromir is a good man, a warrior who has fought Sauron’s forces several times, and who is extremely patriotic. But it is this very patriotism which brings about his downfall. Hoping to save Gondor, he advocates strongly for the Ring to be brought to Minas Tirith and used against the Enemy; he is unwilling to admit that the Ring is not a neutral weapon, that it would only ruin the one who tried to use it even for a good cause[3]. In the end the tug of the Ring overpowers him and he threatens Frodo for it. Again, as with Thorin, it ends with Boromir dying in battle with the Uruk-hai, also after repenting.

Now Frodo is the Ring-bearer and decidedly not evil, and yet he also is in the grey zone. He suffers his moments of weakness just as he triumphs in his moments of strength. In the end, he fails his task, the strength he has previously shown finally deserting him. He claims the Ring for his own, and that one act could have decided the fate of Middle-earth for ill. This leads to my last illustration, Gollum. Gollum began life as a Hobbit named Sméagol, but the Ring inevitably corrupted him. On the one hand, on the Gollum side of his character, he is completely evil: he betrays Frodo and Sam into Shelob’s lair after swearing “on the Precious” to serve Frodo; he is overall driven by the urge to recover the Ring. On the other hand, Sméagol is still existent, albeit barely. When he sees Frodo peacefully sleeping on the Stairs of Cirith Ungol, “[a] strange expression passed over his lean hungry face. The gleam faded from his eyes, and they went dim and grey, old and tired. A spasm of pain seemed to twist him, and he turned away, peering back up towards the pass, shaking his head, as if engaged in some interior debate. Then he came back, and slowly putting out a trembling hand, very cautiously he touched Frodo’s knee – but almost the touch was a caress. For a fleeting moment, could one of the sleepers have seen him, they would have thought that they beheld an old weary hobbit, shrunken by the years that had carried him far beyond his time, beyond friends and kin, and the fields and streams of youth, an old starved pitiable thing.”[4]

As we have seen, J.R.R. Tolkien’s writings are not devoid of complex characters. The Hobbit has at least one, and two if Gollum is counted. The Silmarillion, an intricate work in itself, has many. And three are obvious in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s most popular book and a bestseller for 60 years. My final conclusion is that the claim that Middle-earth has no morally ambiguous characters, that they are all either black or white, is quite false, and that there are no grounds for the accusation.

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (London: HarperCollins, 1990), 233.

[2] In fact, this battle is called the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, or Nirnaeth Arnoediad.

[3] As put forth by Gandalf, Elrond, and Galadriel, at different points in the story.

[4] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Two Towers (London: Unwin-Hyman, 1954), 324.

Benita J. Prins is a writer from Ontario, Canada. She’s loved Tolkien’s works for years, and was inspired by The Lord of the Rings to write her first fantasy novel, Starscape. She blogs at www.benitajprins.wordpress.com.