The BBC’s Jane Ciabattari writes about the ’60s counter-culture influence of J.R.R. Tolkien. It seems a bit of a reach to call Tolkien a figurehead for the movement, but certainly his works struck a chord — and inspired — with people.

The BBC’s Jane Ciabattari writes about the ’60s counter-culture influence of J.R.R. Tolkien. It seems a bit of a reach to call Tolkien a figurehead for the movement, but certainly his works struck a chord — and inspired — with people.

A couple of nitpicks and clarifications:

It’s Middle-earth not Middle Earth.

The note (which is from Letter #226) about the influence of the Somme on the Morannon scenes is incomplete. It reads in full: “The Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme. They owe more to William Morris and his Huns and Romans, as in The House of the Wolflings or The Roots of the Mountains.”

And, as John D Rateliff outlines, Tolkien owned and drove motor vehicles during the 1930s. After WWII he never drove or owned one, having come to grasp “the damage that the internal combustion engine and new roads were doing to the landscape”.

Remember to follow the link at the bottom to read the full article on the Beeb.

Hobbits and hippies: Tolkien and the counterculture

It was a time of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Not to mention protest against the Vietnam War and marches for civil rights and the women’s movement. Who would think a figurehead for this social upheaval would be a tweedy Christian philologist at Oxford?

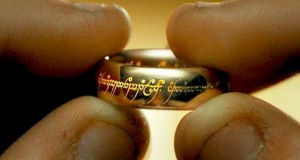

But during the 1960s, a time of accelerating social change driven in part by 42 million Baby Boomers coming of age, Tolkien’s The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings became required reading for the nascent counterculture, devoured simultaneously by students, artists, writers, rock bands and other agents of cultural change. The slogans ‘Frodo Lives’ and ‘Gandalf for President’ festooned subway stations worldwide as graffiti.

Middle Earth, JRR Tolkien’s meticulously detailed and mythic alternate universe, was created against the backdrop of two world wars. As a professor at Oxford , Tolkien taught Anglo-Saxon, Old Icelandic and medieval Welsh and translated Beowulf, which inspired his later monsters. His fantasy vision, and his sense of evil looming over the good life, was shaped by his devout Catholicism and his experience serving in World War I, in which he lost all but one of his close friends.

“The Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to northern France after the Battle of the Somme,” he wrote in a 1960 letter. Frodo and Sam struggling to reach Mordor is a cracked mirror reflection of the young soldiers caught in the blasted landscape and slaughter of trench warfare on the Western Front.

For decades, fans have been obsessed with Tolkien’s Great War of the Ring, with its wizards and magicians, the legions of hobbits, dwarves, elves, orcs, giants, ents, the dragon Smaug guarding his treasure and the threatening Dark Lord. They were popular initially but sales of The Hobbit (published in 1937) and The Lord of the Rings (beginning in 1954) exploded in the mid-1960s, driven by a young generation charmed by Tolkien’s imaginative abundance, the splendour of his tales from a pre-Christian time and his obsessive cataloguing of the history, language and geography of his invented world.

For decades, fans have been obsessed with Tolkien’s Great War of the Ring, with its wizards and magicians, the legions of hobbits, dwarves, elves, orcs, giants, ents, the dragon Smaug guarding his treasure and the threatening Dark Lord. They were popular initially but sales of The Hobbit (published in 1937) and The Lord of the Rings (beginning in 1954) exploded in the mid-1960s, driven by a young generation charmed by Tolkien’s imaginative abundance, the splendour of his tales from a pre-Christian time and his obsessive cataloguing of the history, language and geography of his invented world.

But deeper than this, certain aspects of Tolkien’s worldview matched the perspective of hippies, anti-war protestors, civil rights marchers and others seeking to change the established order. In fact, the values articulated by Tolkien were ideally suited for the 1960s counterculture movements. Today we’d think of Tolkien’s work as being aligned with the geek set of Comic-Con, but it was once closer to the Woodstock crowd. How did this happen?