Passage #4

In describing a fairy-story which they think adults might possibly read for their own entertainment, reviewers frequently indulge in such waggeries as: “this book is for children from the ages of six to sixty.” But I have never yet seen the puff of a new motor-model that began thus: “this toy will amuse infants from seventeen to seventy”; though that to my mind would be much more appropriate. Is there any essential connexion between children and fairy-stories? Is there any call for comment, if an adult reads them for himself? Reads them as tales, that is, not studies them as curios. Adults are allowed to collect and study anything, even old theatre programmes or paper bags.” (57-8)

We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien’s ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children.

We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien’s ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children.

He himself resents the notion; his interest in fairy-stories was not truly piqued until he reached university, he later says. The tone with which he addresses these questions does not dissipate throughout the text; indeed, the questions themselves pop up here and there, and they lead to a discussion not only of the virtues and values of fairy-stories, but even unto one of psychological and sociological proportions.

Passage #5

[Literary belief] has been called “willing suspension of disbelief.” But this does not seem to me a good description of what happens. What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.” (60)

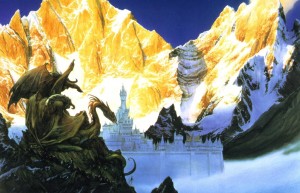

To Tolkien, the successful creation of this Secondary World in literature is the highest art, if not the very “magic” itself. Suspension of disbelief results from a failure on the story-maker’s part, as it thus requires a conscious effort on the part of the reader (and this, being conscious, removes the reader from the Secondary World); acceptance of the Secondary World, or the acceptance of verisimilitude, is what the author hopes to achieve in his audience.

Tolkien says that disbelief is that to which we “descend” when we return to the Primary World and from there look unto the Secondary, instead of immersing ourselves in the latter. His words are harsh here, indeed; but only because immersion in the Secondary World, total immersion, is, as his tomes do attest, perhaps the Professor’s greatest craft and the very reason we choose to read fairy-stories. We experience exactly what he says we should; while in Middle-earth, we are, in fact, in another world, fully accepting of its truths.

It is only when we retire to the Primary World that we reduce this work of art to a scientific endeavor, render it for analysis and scrutiny beyond its verisimilitude. While we are immersed, all that matters is the (literary) present.

Passage #6

Fairy-stories were plainly not primarily concerned with possibility, but with desirability. If they awakened desire, satisfying it while often whetting it unbearably, they succeeded. (63)

Here, the Professor is concerned with issue of belief, specifically on the part of children, in the context of fairy-stories. Children, he notes, are interested in the truth of fairy-stories as similar or different from their world. He posits the theory that belief is not wished for; that, as he says, though he “desired dragons with a profound desire,” he “did not wish to have them in the neighbourhood, intruding into [his] relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear” (64).

The desire, the window into a tempting “Other-world” of wonder in both beauty and fear that Fantasy provides, that is what’s important. This is but a fragment of a much larger section dealing mostly with the works of famous children’s book author Andrew Lang, which Tolkien analyzes both from his childhood perspective and that of his present adulthood; it is quite an interesting bit of scholarship for Tolkienites, since many of us, like the Professor, grew up with a love of Fantasy that has changed and matured as we have.

Passage #7

The process of growing older is not necessarily allied to growing wickeder, though the two do often happen together. Children are meant to grow up, and not to become Peter Pans. Not to lose innocence and wonder, but to proceed on the appointed journey…But it is one of the lessons of fairy-stories (if we can speak of the lessons of things that do not lecture) that on callow, lumpish, and selfish youth peril, sorrow, and the shadow of death can bestow dignity, and even sometimes wisdom. (66-7)

I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the “allegory-application” debate) is clearly evident.

I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the “allegory-application” debate) is clearly evident.

I find this inherent contradiction in Faërie to be one of Tolkien’s prime occupations throughout the work; Faërie, if nothing else, is full of dichotomies: it is both beautiful and dangerous, it is for pleasure and for learning, it is for children and adults. Yet where does the Professor ultimately settle on these issues?