Let ‘forge the golden dwarf’, join ‘jump the shark’, and ‘nuke the fridge’ in our lexicon for describing when a once-great creative force reveals itself truly spent.

Let ‘forge the golden dwarf’, join ‘jump the shark’, and ‘nuke the fridge’ in our lexicon for describing when a once-great creative force reveals itself truly spent.

The Desolation of Smaug, and the Hobbit trilogy as a whole, only makes sense as the world’s most expensive satire on the vast canvas of a contemporary film industry increasingly supported by so-called ‘tentpole blockbusters’. In true Kiwi fashion, the trilogy achieves this through an amazing capacity to laugh at itself… but quite literally at the audience’s expense.

In this satire, Bilbo – the ‘everyman’ protagonist – represents the average ticket-buying punter. The punter is convinced by some marketing wizard suggesting that in December 2012, and again in December 2013 and ‘14, that they will have a chance to join in an adventure. There is then an interminably long period of waiting – the only excitement being the occasional expository video blog laying out how the adventure will be undertaken.

On the announcement that the duology will become a trilogy, our punter expresses doubt that the source material can support three films, but is quickly trolled on the internet by fanatics of the first trilogy (‘fan’ is of course derived from the word ‘fanatic’). To be clear, in this case fanatics are those people who probably own elf ears, refer to the director as ‘PJ’ as if he is as close to them as their favourite pair of pyjamas and who, like trolls, would in all likelihood turn to stone if they were ever exposed to daylight.

There was a little Rivendellian hope in the early trailers for the first film, trailers that gave the impression that there had been no drop off in quality from the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Optimism was briefly restored.

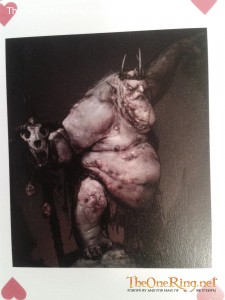

The adventure finally got underway proper when, at long last, our punter made his way to the local multiplex in December 2012. Cue three hours of anaemic and contrived drama intercut by rock transformers, CGI goblins and computer game physics, with the main abomination being the Great Goblin of 48fps, which while hyped, proved utterly anti-climatic. Our punter is left with a ringing in his ears, and senses he’s had a different experience of the film from those around him when the lights come back on. He notes that they all have beards and look as though they spend a lot of time underground. These are the fanatics, and he realises with a sigh that they’ll be with him for the whole journey.

The adventure finally got underway proper when, at long last, our punter made his way to the local multiplex in December 2012. Cue three hours of anaemic and contrived drama intercut by rock transformers, CGI goblins and computer game physics, with the main abomination being the Great Goblin of 48fps, which while hyped, proved utterly anti-climatic. Our punter is left with a ringing in his ears, and senses he’s had a different experience of the film from those around him when the lights come back on. He notes that they all have beards and look as though they spend a lot of time underground. These are the fanatics, and he realises with a sigh that they’ll be with him for the whole journey.

Following this first film, our redoubtable punter watches the fanatics climb trees to escape the snarling pack of critics whose opinions they deem below them anyway. However, recognising they were outnumbered, the fanatics avoid a fight and instead fly off to concentrate on how awesome the next film will be.

Enthusiasm for the second film is then notably down, with the prognosticators bearish about its prospects. Ever the true trooper, our everyman ignores the warnings and regardless, returns to the cinema in December 2013, along with the fanatics. But already alarmed by his experience in the darkness of the cinema in 2012, he quickly discerns that there is some strange power afoot. Clearly, the once fresh and new ‘Wellywood’ has now aged, becoming a place where the writing team repeat themselves from the earlier successful trilogy, and are clearly lost with regard to what and who the film is about, and who is the films’ intended audience. The murkyness that has descended on the story-telling capacity of once great filmmakers may have its source far away, in an old fortress – Hollywood – where a powerful eye looks outwards from MGM-Warner Bros-New Line.

No turning back

But having come this far, there is no turning back. Our everyman is a captive audience, having already put down money for tickets for the first two films. He will barrel on – with the fanatics he now has for company – and be back in 2014 regardless. And no doubt the next film will be another fishy outing, with the online community continuing to search for the silver lining to the new trilogy and increasingly finding themselves cut off from the mainland of opinion, too in denial about how they’ve been let down to even complain about their lot.

But having come this far, there is no turning back. Our everyman is a captive audience, having already put down money for tickets for the first two films. He will barrel on – with the fanatics he now has for company – and be back in 2014 regardless. And no doubt the next film will be another fishy outing, with the online community continuing to search for the silver lining to the new trilogy and increasingly finding themselves cut off from the mainland of opinion, too in denial about how they’ve been let down to even complain about their lot.

When the journey itself is finally over and we’ve arrived at our destination, we’ll see what lies at the end: a great, sadly self-indulgent dragon sitting on a pile of gold. Peter Jackson is indeed the King under the Mountain – the lonely mountain that may now count as New Zealand’s film industry. (For what is often lost in all the focus on Jackson’s ‘Wellywood’ is how it may, like Smaug firestorming Erebor, have sucked the air out of the Kiwi film industry, one that no longer seems to forge great films telling New Zealand stories, films like Once Were Warriors. Instead, there’s just Peter Jackson sitting on a heap of gold from making films informed by a North American cinematic sensibility.)

Hollywood is the Mirkwood of the 21st century, a dark rising force ruthlessly in pursuit of the money to be made in unoriginality and bloat: adaptations, sequels/ prequels, remakes and the splitting of films into twos or threes.

The Hobbit trilogy is, of course, all of these things. It has been sold as an adaptation, and a prequel to the Lord of the Rings. In its content, where it diverges from the source material, it appears to be largely rehashing the best bits of the first trilogy. And of course, the Hobbit has also been split twice, without adding anything of quality to the story.

As a consequence, for laying waste not only to Tolkien’s work, but also for brazenly taking the audience for a ride when in fact they were promised a journey, the Kiwi dragon must be shot down. This review is a black arrow. And like a black arrow, it appears to be a rare thing, especially on theonering.net.

Unlike the eponymous dragon, who had only one weak spot, it is hard to know where to begin in eviscerating this flatulent mess of a film. That the Desolation of Smaug diverges significantly from both the letter and spirit of the book on which it is based is not in itself the problem, although for anyone hoping to see the essence of the Hobbit captured on film, or even memorable scenes translated to screen, it must surely be a great disappointment. Rather, it is that it diverges so unimaginatively, inconsistently and pointlessly. As a film, even as one that sits in the middle of a trilogy, it is just a bad film, with a lazily conceived focus and structure, poor editing, dialogue and an injudicious use of effects.

Where is The Hobbit?

The title of the trilogy is ‘The Hobbit’, and yet Bilbo is barely the central focus, and when he is it often feels contrived and arbitrary. When he does play an active and necessary role his action is then rendered redundant by the events that follow. He rescues the dwarves from the spiders, but then the elves appear and do the same thing; he helps them escape the elves, but then Kili opens the second gate in a far more heroic manner; he has the bravery to confront Smaug, but then all the dwarves do the same. Indeed, much as in the first film, there is simply no sense of who the primary protagonist is supposed to be. The dwarves get more screen time than Bilbo. Bard – a tertiary character – gets more scenes than virtually any individual dwarf. Legolas, a character not even in the book, gets arguably more than Bard. And Tauriel, who is not only not in the book but also not in any Tolkien, gets more than Legolas. Who exactly is this film about?

The title of the trilogy is ‘The Hobbit’, and yet Bilbo is barely the central focus, and when he is it often feels contrived and arbitrary. When he does play an active and necessary role his action is then rendered redundant by the events that follow. He rescues the dwarves from the spiders, but then the elves appear and do the same thing; he helps them escape the elves, but then Kili opens the second gate in a far more heroic manner; he has the bravery to confront Smaug, but then all the dwarves do the same. Indeed, much as in the first film, there is simply no sense of who the primary protagonist is supposed to be. The dwarves get more screen time than Bilbo. Bard – a tertiary character – gets more scenes than virtually any individual dwarf. Legolas, a character not even in the book, gets arguably more than Bard. And Tauriel, who is not only not in the book but also not in any Tolkien, gets more than Legolas. Who exactly is this film about?

The film itself also has no arc – no beginning or end. The anti-climatic escape at the end of the first film (anti-climatic as the villain was not defeated) was, it turns out, not an end at all, for the opening scenes of the second film continue with the company being chased by precisely the same orcs and wargs that they had just escaped in the previous film. Almost three hours later, with a natural climax again being denied and replaced by a wholly fabricated action sequence that, like the first film, resolves and achieves nothing but to pad things out, the film ends arbitrarily, with literally nothing resolved.

More pronounced than this was the sloppy editing. How is it that Azog is called away during the night from Beorn’s house, only to arrive at Dol Guldor seemingly before the Dwarves and Hobbit wake up the next morning? Why could he not have been shown arriving at Dol Guldor sometime after the Company reach Mirkwood, suggesting a passage of time? This gets at the major puzzle of this film: despite having almost three hours to tell a few short chapters of a quite small book, the whole thing feels rushed. There is barely a moment to linger. Indeed, the filmmakers appear to have been happy to shoe-horn in untold numbers of absurd and unnecessary action sequences at the expense of scenes that would make us care about the characters involved in the action.

The dialogue, like in the first film, sounds as though it was written by a sleep-deprived student an hour before a deadline, hoping that no one will notice the logical fallacies. Evidence of this is stark from the beginning: ‘Did they see you?’ asks Gandalf of Bilbo, when he has been on the look-out for the orcs hunting them. ‘No’, replies Bilbo. ‘What did I tell you? Quiet as a mouse!’, Gandalf concludes. This is arguably bad dialogue – a lazy confusion of a visual and aural reference. More strangely, in many places original dialogue has been replaced with fan-fiction dialogue, much of which is repetitive or redundant. Admittedly this is all not so unexpected given the dialogue in the first film, from old Bilbo’s verbose opening narration to Gollum’s suggestion that he would eat Bilbo ‘whole‘ (how could he eat a Hobbit whole? Raw, perhaps. But not whole)

And then we get to the special effects. The use of CGI is so pervasive in this film that for whole sections it appears to be an animated feature, with obviously digital backgrounds and – for the long shots – almost wholly digital characters. A digital orc has none of the weight or sense of threat of a prosthetics-clad actor. While the effects are some of the best ever put on screen, they are a poor substitute for prosthetics, animatronics and realistic physics. While the dragon and the spiders were very well conceived and executed, the problem with CGI became much more evident on those scenes were clearly less care was taken.

Moments of wonder

This is not to say there are not moments of wonder in the film. Overall, the set design was excellent. The panoramas were often breath-taking, even if the director himself appears rather too enamoured by New Zealand’s mountain vistas (or perhaps too indebted to the New Zealand Tourism Minister – who also moonlights as the Prime Minister – for giving the production massive tax-breaks to risk cutting back on the free advertising for the country), at the expense of a focus on characters. The acting generally was solid, despite the phoned-in dialogue and – in the dwarves case – little to do but react to monsters that would be digitally added later.

This is not to say there are not moments of wonder in the film. Overall, the set design was excellent. The panoramas were often breath-taking, even if the director himself appears rather too enamoured by New Zealand’s mountain vistas (or perhaps too indebted to the New Zealand Tourism Minister – who also moonlights as the Prime Minister – for giving the production massive tax-breaks to risk cutting back on the free advertising for the country), at the expense of a focus on characters. The acting generally was solid, despite the phoned-in dialogue and – in the dwarves case – little to do but react to monsters that would be digitally added later.

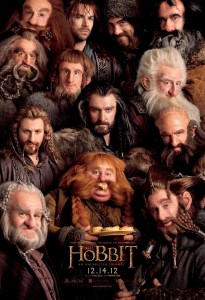

On the subject of the dwarves, it is now clear that the film’s problems on screen almost all come back to the attempt to flesh out each of the thirteen as characters in their own right. This is arguably the worst single decision of the whole production, and it is borne by the films like a great prosthetic albatross. There are several reasons why this was a bad decision. First, with the exception of long-shots, it is virtually impossible to get all the dwarves on screen at the same time without making them looking like a terrified huddle of children (not helped by their relatively small stature when around elves and men), clinging together for warmth and protection. This manner of getting them all into the picture strips them of all sure-footed, four-square dignity – the quality that dwarves are most meant to embody. Even if this wasn’t the problem, for the viewer there is, regardless, simply too many characters on screen in such scenes to register what is going on. Furthermore, the attempt to flesh out their characters falls flat, because ultimately they individually serve little purpose to carry the plot forward.

Given the sheer number of changes made to the original book, it is thoroughly bizarre that the filmmakers didn’t make one bold one at the outset with regard to how the dwarves are handled, which would have made the rest of the story far more cinematically tractable, not to mention less of a logistical headache. Three more effective alternatives come to mind.

What were the dwarfternatives?

First, the majority of the company could have been treated as they were by Tolkien in the book – as extras rather than characters in their own right. The point of the dwarves all having such similar names is to illustrate that they are, to Bilbo, one big indistinguishable rabble. The filmmakers would arguably have done better to have emphasised how similar most the dwarves are, and keeping them as an inscrutable pack of foreigners to Bilbo. The entire book is about someone taken out of their comfort zone and whisked away on an adventure into a world that is utterly alien to him. They could have had a running joke in the films where Bilbo keeps confusing all the dwarves, which would have relaxed the audience and made them realise that they are not expected to know who they all are, as Bilbo doesn’t either.

First, the majority of the company could have been treated as they were by Tolkien in the book – as extras rather than characters in their own right. The point of the dwarves all having such similar names is to illustrate that they are, to Bilbo, one big indistinguishable rabble. The filmmakers would arguably have done better to have emphasised how similar most the dwarves are, and keeping them as an inscrutable pack of foreigners to Bilbo. The entire book is about someone taken out of their comfort zone and whisked away on an adventure into a world that is utterly alien to him. They could have had a running joke in the films where Bilbo keeps confusing all the dwarves, which would have relaxed the audience and made them realise that they are not expected to know who they all are, as Bilbo doesn’t either.

Second, they could have kept the introduction of the dwarves at Bag End, but then whittled down the company by having one die at each encounter with danger – one with the trolls; one with the goblins; one with the wargs; one with the spiders; two with Smaug (eaten with the ponies); three at the battle of the five armies. At the end, there could be left Gloin, Balin and Ori, as all three are relevant to Lord of the Rings, and Bombur, as he would be the least likely to survive. Killing off the dwarves would have created a sense of something at stake throughout the films, which was utterly lacking throughout. Kili’s leg injury in the Desolation of Smaug was frankly a feeble attempt to raise the stakes.

Third, and perhaps most plausibly, the Company of Dwarves could have been reduced to seven at the outset. These seven could have been the ones who actually have relevance to the plot of the book: Thorin, Fili, Kili, Balin, Gloin, Dori and Bombur. With the exception of Fili and Kili, this company would also have the advantage of distinct and thus memorable names. In combination with Gandalf and Bilbo, this makes a company of nine, which would have a pleasing symmetry with the Lord of the Rings. And as we know from the previous trilogy, a company of nine fits the cinema screen quite nicely.

In the end, however, none of these options were tried, and the result is the filmmakers resort to all sorts of otherwise redundant scenes simply to give the rabble something to do. The result is the unwieldy and unfocused shambles we see on screen.

Parallels with the decline of George Lucas

The saddest yet most obvious conclusion from another three hours in Middle-earth is that Jackson clearly shot his bolt with Lord of the Rings. What he now directs are overly produced set pieces, with little room for characters or narrative. He no longer knows when to leave something alone, visually or narratively. Characters are not given time to breathe; action sequences remain unengaging animated blurs, and go on far too long. Smaug’s mystique and grandeur is utterly destroyed in the final confrontation with the dwarves, convoluted scenes that include not one but two scenes that are Jackson’s own ‘jump the shark‘ and ‘nuke the fridge‘ moments, in the case ‘jump on the dragon’s nose‘ and ‘forge the golden dwarf’.

The saddest yet most obvious conclusion from another three hours in Middle-earth is that Jackson clearly shot his bolt with Lord of the Rings. What he now directs are overly produced set pieces, with little room for characters or narrative. He no longer knows when to leave something alone, visually or narratively. Characters are not given time to breathe; action sequences remain unengaging animated blurs, and go on far too long. Smaug’s mystique and grandeur is utterly destroyed in the final confrontation with the dwarves, convoluted scenes that include not one but two scenes that are Jackson’s own ‘jump the shark‘ and ‘nuke the fridge‘ moments, in the case ‘jump on the dragon’s nose‘ and ‘forge the golden dwarf’.

To be fair, it could simply be that too many pieces of a big machine were already in motion when he came onboard following the departure of the original director Guillermo del Toro. Jackson may simply have had insufficient time to prepare. He himself has admitted he had five months to prepare, whereas for the Lord of the Rings he had two years, and the lack of planning is evident throughout the production, notable for its reshoots and pickups and changes to both plot and design.

But what seems more likely to account for this dramatic train-wreck of a trilogy is that Jackson has simply followed the career trajectory of George Lucas. Both conceived and directed revolutionary trilogies when under pressure to meet tight budgets while also trying to establish their reputations. But on the back of their original success, both men then built isolated empires to blockbusting filmmaking, and like the dragon Smaug, appear to have become transfixed by the toys they have collected.

Both men explicitly set out with their second trilogies to ‘revolutionise the cinema experience’, rather than to simply make good movies. As such, Jackson and Lucas both ended up with a keener interest in the process rather than the product. Indeed, with its use of cutting edge technology – Red Epic HD cameras, 3-d, forty-eight frames a second; motion capture – the Hobbit films appear to be more a show-reel for Weta Digital and the new technology put to work in making the film, and a tribute to earlier successes, rather than dramatic works in themselves.

The fanatics appear to be defending the first two films by arguing that you can’t perfectly adapt a novel – changes must be made. Undoubtedly. But the Desolation of Smaug is simply a poorly written and directed film, full stop. It had all the other necessary ingredients – fantastic design, excellent acting, classic source material – but the balance and marshalling of these ingredients is all wrong. And as any cook knows, it is balance as much as substance that matters when concocting anything that leaves people wanting more. The Desolation of Smaug is a salutary lesson that quantity simply can’t stand in for quality.

Thomas Monteath is a British academic and can be reached at thomasmonteath@gmail.com.