Tolkien’s love of Anglo-Saxon history is well-known, as are his influences from such Nordic works as Beowulf and the Finnish Kalevala. His passion for these cultures is evident in every race he created for Middle-earth, including the dwarves. Yet as has been highlighted in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, some of the inspiration for the dwarven race may have come from an understated influence: the Celts.

Like the dwarves of Erebor, the Celts were a group of people renowned for their warriors who were forced to flee their mountainous homeland in the east due to unknown strife around 1600 BCE (the Bronze Age). Spilling into Europe, the Celts wandered for generations, making their way west to the British Isles. It is worth noting that the term “Celts” applies to several groups of un-unified peoples who, much like the dwarves, were prone to both fighting against each other and in turn, banding together to unite against a common enemy, such as the Roman legions.

When comparing the Celts to dwarves, it is important to focus on one of the northern tribes (in modern Scotland): the Picts. They were given their name by the Romans, who found the animal shapes and designs they painted on their bodies with blue woad to be curious pictures. The Celts were also in the habit of shaping their hair before battle – using a mixture of lime and urine as a sort of styling clay that caked white onto their tresses and made their hair stand on end. For a cinematic example of these ancient warriors, check out the trailer for Kevin MacDonald’s adaptation of The Eagle (2011).

The Eagle (2011)

If the interviews with Billy Connolly from last summer are still accurate, then we can expect Dáin Ironfoot to “have a Mohawk and tattoos on my head…I arrive riding a wild pig.” Sound familiar?

It should also be noted that as a Scot, Connolly himself is a Celt. In fact, many of the actors portraying dwarves in The Hobbit are of Celtic descent, and several were allowed to keep their respective accents. James Nesbit’s Bofur speaks in his Northern Irish brogue, and Graham McTavish’ Dwalin (who also bears war-paint like tattoos) sounds like the Scot he is. Aidan Turner, Kili, is an Irishman, Dean O’Gorman, playing his brother Fili, is a Kiwi of Irish descent, and Ken Stott (Balin) is another Scotsman.

As an interesting side note, belonging to the Order of Fili (wisemen and poets) was required for a warrior to enter Ireland’s elite Fenian ranks. Kili, similarly, could be argued as an alternate spelling/pronunciation of the common Irish surname Kelly, which means warrior (and is coincidentally why I was given my TORn nickname, since it is my birth name). Naming the two youngest of Durin’s heirs names that invoke a warrior heritage makes sense, however, it is unknown if Tolkien was aware of these linguistic connections.

Any listener of The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey Special Edition soundtrack will know that the track “Erebor” begins with a proud bagpipe solo: a clear nod to the Scottish. Artist John Howe makes several references to Celtic inspiration in the first Hobbit Chronicles book, citing references to both Kili’s flip knife and Ori’s board game as being based on Celtic artifacts.

Even Celtic dress sounds similar to that of the dwarves: “In terms of clothing, the Celtic women wore a simple long garment with a cloak. The men wore trousers (sometimes knee length), a sleeved tunic reaching the thigh, a cloak, and sandals or boots. A metal piece of jewelry for around the neck called a torc (torques) was quite popular. Clothing dyed in bright colors was common. Men wore droopy mustaches, sometimes beards, and often long hair, all of this in contrast to the contemporary Romans.”

An artist’s rendition of male Celtic dress

However, the Celtic link to the dwarves in Tolkien’s writing isn’t as obvious as the Nordic influences, so why did the filmmakers take this route?

The easy answer is because it hasn’t been done yet. None of the races previously explored in Jackson’s Middle-earth had a Celtic slant, and identifying the dwarves with the proud warriors of the Celts distinguishes them as a race and culture apart from the rest, especially where the Picts are concerned.

The dwarves are from the north, just as Scotland is north of England, the nation that is conceivably Tolkien’s main inspiration for Middle-earth. More than any other race, Tolkien’s dwarves link their existence with the mountains, very much like Highlanders. Also like the Highlanders, Dáin and his people are renowned for their endurance, running for days to come to Thorin’s aid.

Similarly to the Dwarves, the land of the Picts was under constant threat. While such a military force may seem unimpressive by today’s standards, imagine yourself back at the dawn of the Common Era when the world was a much quieter place. The roar of a Roman cavalry charge echoing across the land like earthen thunder would have been much like the advance of Smaug. The armor of the legionnaires glinted in the sunlight like so many serpentine scales. Such a monstrous force was hitherto unknown to the indigenous Britons and was, understandably, often likened to a dragon.

Smaug the Terrible is very much a metaphor for warfare and greed. Just as the Roman invaders laid waste to villages and scattered tribal peoples, so did the dragon. The Romans modified Britain’s landscape and scoured the land for natural resources, just as Smaug scorched the earth and hoarded the treasure of the dwarves.

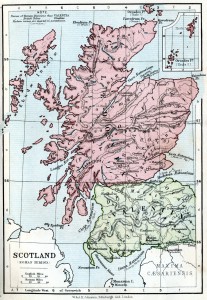

Scotland in the Roman era

The Picts, like Durin’s folk, stood strong against the Roman dragon and slaughtered entire legions and then some. Unable to subdue the northern tribes, Emperor Hadrian began construction on a massive wall to keep the tribes out of the fertile lands of England in 122 CE. This wall is known as Hadrian’s Wall and its remnants remain near the modern Scottish-English border. Had the dwarves ever turned on the race of Men, such a measure would have probably been taken!

Ruins of Hadrian’s Wall

Tolkien would have been well-aware of this history, and in fact, even his beloved Anglo-Saxons found the Celts to be formidable opponents. The Icelandic sagas written in the 13th century warn their people not to go to Scotland if they wished to live. One Scot in the saga, said to be Grjotgard, a kinsman of Melkolf (the king of Scotland), was quoted as saying to the Saxons: “You have two choices. You can go ashore and we will take all your property, or we’ll attack you and kill every man we lay our hands on.”

Given that the tale survives, it’s not difficult to tell which option the Icelandic warriors chose. It also isn’t difficult to imagine Thorin Oakenshield issuing such an ultimatum to invaders.

We must await the next two films to see what further Celtic traits will be shown through the dwarves. But as a Celt myself, I applaud Jackson and Weta’s decision to explore a facet of British culture that was previously understated in Tolkien.

Staffer Kili is one-half of the TORn Happy Hobbit crew. The views and opinions presented in this article are her own, and do not necessarily represent those of TheOneRing.net or its staff.