During the first month of this century, Tolkien fans were asking the following questions to our Green Books staff at TheOneRing.net…

Q: Dear Everybody, I was just curious as to when it is Frodo’s and Bilbo’s birthday according to our calendar? I really enjoy your site, keep up the great work.

Q: Dear Everybody, I was just curious as to when it is Frodo’s and Bilbo’s birthday according to our calendar? I really enjoy your site, keep up the great work.

– Dan

A: Frodo and Bilbo shared their birthday on September 22nd, as stated in “The Long-Expected Party.” The Hobbits called this month Halimath. The duration of the solar year for Middle-earth was the exact same as that of our Earth; namely 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds (see Tolkien’s note in The Return of the King, Appendix D, “Shire Calendar”). So we are basically measuring the same span of time but with a different enumeration of days. Small differences in each month’s duration make it a little tricky to compare the Shire Calendar to our Gregorian Calendar. We have months with 28, 30, or 31 days, but every Shire month is exactly 30 days. But look very closely, and you’ll see Tolkien added days like 1 Yule, 2 Yule, the Midyear’s Day, etc. It’s enough to cross your eyeballs!

I managed to do a simple overlay of our current year 2000 (which is a Leap Year here in the United States) with the Shire Calendar table. I added the Overlithe holiday the Hobbits would have used for their Leap Year (as we would add February 29th) and counted forward to find the equivalent of Halimath 22nd. It turns out Frodo and Bilbo’s birthday falls on the day we call September 23rd… at least this Leap Year. Any other year it would fall on September 22nd. But don’t ask me to calculate for the Chinese or Hebrew calendars, I claim no talent in mathematics!

Update!

I saw the question you answered about Frodo and Bilbo’s birthday in relation to our calendar, and looked it up in Appendix D. I noticed that it says that the hobbits’ Midyear’s Day corresponded to the summer solstice, making our New Year’s Day the hobbits’ January 9. Therefore, Bilbo and Frodo’s birthday would be September 12th (13th in leap years).

– David Massey

Interesting process of calculation, David! I am afraid I’ve spent too many years counting my own branches and little else, leaving me ill-equiped for higher forms of algebra.

Q: I got a question in reference to the historic background Tolkien might or might not have used. In particular I was wondering about Gondor and Minas Tirith and if there was correlation between that and the Byzantine Empire. Especially since Byzantium was seen as sort of the last hope for Christianity in the east? Anyway, it seems logical to me, but I was wondering if there was any actual written evidence of a correlation there.

Q: I got a question in reference to the historic background Tolkien might or might not have used. In particular I was wondering about Gondor and Minas Tirith and if there was correlation between that and the Byzantine Empire. Especially since Byzantium was seen as sort of the last hope for Christianity in the east? Anyway, it seems logical to me, but I was wondering if there was any actual written evidence of a correlation there.

–John Simmons

A: To draw any specific correlation between the history of the imagined world of Middle-earth, and the history of Europe, invites problems—which is not to say that certain connections do not exist, but they are easily misinterpreted or over-analyzed. Treading softly in answer to this question, I note that Tolkien wrote in a letter that “the action of the story takes place in the North-west of ‘Middle-earth’, equivalent in latitude to the coastlands of Europe and the north shores of the Mediterranean… If Hobbiton and Rivendell are taken (as intended) to be at about the latitude of Oxford, then Minas Tirith, 600 miles south, is about at the latitude of Florence. The Mouths of Anduin and the ancient city of Pelargir are at about the latitude of ancient Troy… The progress of the tale ends in what is far more like the re-establishment of an effectively Holy Roman Empire with its seat in Rome.” (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 376). In Tolkien’s long letter to Milton Waldman (also in The Letters of JRRT), Tolkien explicitly makes a correlation of Gondor to Byzantium, writing that “in the south Gondor rises to a peak of power, al most reflecting Númenor, and then fades slowly to a decayed Middle Age, a kind of proud, venerable, but increasingly impotent Byzantium.” (p. 157).

– Turgon

Q: Celeborn led the attack on Dol Guldur during the War of the Ring. Is there any book that describes this battle?

Q: Celeborn led the attack on Dol Guldur during the War of the Ring. Is there any book that describes this battle?

–Tim

A: The only account I find of this conflict is in The Return of the King, Appendix B, “The Tale of Years.” Look on page 375 to learn more of the force commanded by Celeborn and Galadriel. You can find further synopsis and a map with dates and movement of troops in The Atlas of Middle-earth by Karen Wynn Fonstad, on page 150, “Battles in the North.”

Q: Since Elrond and Galadriel have great rings can they not perceive each other? Why then is the Fellowship not welcome in Lothlórien? Why the blindfolds and surprise to see Gimli? Can’t Elrond communicate this through the rings without sending messengers?

Q: Since Elrond and Galadriel have great rings can they not perceive each other? Why then is the Fellowship not welcome in Lothlórien? Why the blindfolds and surprise to see Gimli? Can’t Elrond communicate this through the rings without sending messengers?

– Trevor Price

A: This is indeed a seeming paradox. Let’s take it one at a time. Firstly, about the Fellowship’s welcome in Lothlórien. If you read carefully, the Elves on the borders of Lórien, though at first suspicious, welcome the Company as graciously as they may and try to be courteous. They are willing to receive them and host them, though this is partly because Legolas is with them. They speak of Elrond’s messengers passing by Lórien on their way home up the Dimrill Stair. These are the Elves, you remember, that Elrond sent out to scour the countryside for sign or news of the Black Riders before he would allow the Company to set out, so they were not sent expressly for the purpose of telling those in Lórien about the Company. Okay, to answer the next points about the blindfolds and the surprise to see Gimli, I’ll have to work backwards. Galadriel and Celeborn already knew who and what were each member of the company. But, the border guards didn’t. When they saw a dwarf, they followed the law of the land, which stated that he wouldn’t even be allowed to enter Lothlórien. It was only on the say-so of Aragorn and Legolas that they let him in at all, because they were simply following the rules and didn’t know how a dwarf would be received in the City of the Galadhrim. “A dwarf!” said Haldir. “That is not well… they are not permitted in our land. I cannot allow him to pass… very good… we will do this, though it is against our liking. If Aragorn and Legolas will guard him, and answer for him, he shall pass; but he must go blindfold through Lothlórien.” So you see, their information was incomplete, but later we see that Galadriel had full information. Elves come out the forest and bring messages to Haldir. “Also, they bring me a message from the Lord and Lady of the Galadhrim. You are all to walk free, even the dwarf Gimli. It seems that the Lady knows who and what is each member of your Company. New messages have come from Rivendell perhaps.” *Perhaps.* Haldir really didn’t know how the Lady got her information, he just knew enough to know that she knew there was a dwarf in her land and she was commanding that he be allowed to walk free. For all we know, these messages may have come through the power of the rings. But here’s another question to throw on the fire. Is it really the rings which convey the power of communicating with thought? Does Tolkien actually state that? The quote runs thusly: “Often long after the hobbits were wrapped in sleep they would sit together under the stars, recalling the ages that were gone and all their joys and labours in the world, or holding council, concerning the days to come. If any wanderer had chanced to pass, little would he have seen or heard, and it would have seemed to him only that he saw grey figures, carved in stone, memorials of forgotten things now lost in unpeopled lands. For they did not move or speak with mouth, looking from mind to mind; and only their shining eyes stirred and kindled as their thoughts went to and fro.” Keep in mind that we are not speaking only of Gandalf, Elrond, and Galadriel, but also of Celeborn, who did not hold a ring. So was this a power of the rings that came to Celeborn by extension through Galadriel, or was it a power of the Eldar and of Gandalf as a Maiar? Tolkien doesn’t really say. So while I’m sure they used messengers when it suited them, I’m also willing to bet that Galadriel and Elrond and Celeborn, between them, had other ways of communicating, and since Tolkien didn’t specify how she got her information, we don’t really know how Galadriel knew what was going on. Also, don’t forget that Lothlórien was built and defended largely with the power of Galadriel’s ring, and I suspect that she had power to see what was passing on the borders of her land, possibly in the Mirror. So she had many ways of gathering news, and we’re left not knowing whether the telepathy was a function of the rings or a function of the minds of Eldar and Maia.

– Anwyn

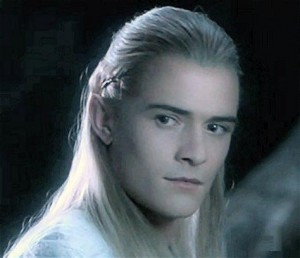

Q: What happened to Legolas? Did he eventually go over the Sea like the others? And could Sam have also gone at some later date?

Q: What happened to Legolas? Did he eventually go over the Sea like the others? And could Sam have also gone at some later date?

–Judith A. Sullivan

A: Yes, and yes. Return of the King states in various places what happened to each member of the Company and especially those who had earned the privilege of sailing over-sea. The Tale of Years states it the most concisely. The entry for Shire-year 1482 runs thusly: “Death of Mistress Rose, wife of Master Samwise, on Mid-year’s Day. He comes to the Tower Hills, and is last seen by Elanor, to whom he gives the Red Book afterwards kept by the Fairbairns. Among them the tradition is handed down from Elanor that Samwise passed the Towers, and went to the Grey Havens, and passed over Sea, last of the Ring-bearers.” So it is oral tradition and not documented fact, but it seems logical and likely. Tale of Years goes on, with the entry for 1484 speaking of the deaths of Eomer, Merry and Pippin, and then the entry for 1541: “In this year on March 1st came at last the Passing of King Elessar. It is said that the beds of Meriadoc and Peregrin were set beside the bed of the great king. Then Legolas built a grey ship in Ithilien, and sailed down Anduin and so over Sea; and with him, it is said, went Gimli the Dwarf. And when that ship passed an end was come in Middle-earth of the Fellowship of the Ring.” So it is fact that Legolas went over Sea, and again oral tradition that Gimli went with him. In another place it is speculated that Galadriel remembered Gimli and obtained the grace for him to sail.

– Anwyn

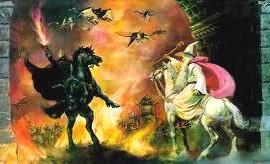

Q: Gandalf the Grey held Weathertop against 5 Black Riders. Later at Minas Tirith when he is Gandalf the White he concedes in discussions with Denethor that he may not be equal to the Witch-king. I realize that Gandalf using his power for defense only. However, he let the Witch-king break through the first level of Minas Tirith. How can these facts be reconciled?

Q: Gandalf the Grey held Weathertop against 5 Black Riders. Later at Minas Tirith when he is Gandalf the White he concedes in discussions with Denethor that he may not be equal to the Witch-king. I realize that Gandalf using his power for defense only. However, he let the Witch-king break through the first level of Minas Tirith. How can these facts be reconciled?

–Trevor Price

A: Okay, my answer here has multiple points. (A) At Weathertop, the objective was for Gandalf not to be captured or killed, not for him to kill the Witch-King or any other Nazgûl. I think it is safe to say that even if Gandalf might or might not have killed a Nazgûl in single combat, he is capable of defending himself against five of them. (B) At Minas Tirith, it was not the Witch-king on his lonesome who broke through the first circle of the City, and as a matter of fact, they *didn’t* break through the first circle. They broke through the wall of the Pelennor, many miles from the City, and used catapults to throw what amounted to bombs and also human heads over the wall of the City and *into* the first circle. This doesn’t mean an enemy ever set foot into the city. Gandalf met the Witch-king in the Great Gate, after the battering-ram had done its work on the Gate itself. So you see, it was the power of Sauron’s armies that got them past the wall, over the fields, and on to break down the Gate. The Black Rider expected to ride right in through the Gate, obviously, but Gandalf was there to stop him. In the end, the sudden arrival of the Riders of Rohan made the Witch-king feel it was not the right time to continue to challenge the White Rider, and he “left the Gate and vanished.” So in neither of these cases was the objective of Gandalf the death of the Witch-king. He knew of the prophecy that not by the hand of man would he fall, and his objective was merely self- and City-preservation. He blocked the Rider’s entry into the Gate and he escaped Weathertop with his life.

– Anwyn

![]() Q: There is a question that has always bothered me since reading the Silmarillion. The great strength of Gondolin was its secrecy. That secrecy had long been preserved by the vigilance of the Eagles that kept a look out for Morgoth’s spies. The Eagles were sure enough of themselves to declare that if it were not for their watch, then long ago Gondolin would have been discovered. They were sharp enough to see and even recognize individuals such as Hurin after his release from Angband. What happened to the Eagles that were keeping watch on the borders of Gondolin when Morgoth’s army arrived? I understand that Turgon and the Gondolindrim had been warned by the Valar via Ulmo’s message given to Tuor and that Maeglin betrayed the location of the city to Morgoth. However, once that message that the city was not long to last was delivered and Maeglin’s treason accomplished, were the Eagles released from their watch on Gondolin? If the Eagles were at the bidding of Manwë did he know that they were not going to be able to keep guard and that is why he sent Tuor? I guess I just don’t understand how one minute no spy of Angband can get near the place unnoticed and the next a whole army of orcs, dragons, and balrogs gets to the city walls without any warning

Q: There is a question that has always bothered me since reading the Silmarillion. The great strength of Gondolin was its secrecy. That secrecy had long been preserved by the vigilance of the Eagles that kept a look out for Morgoth’s spies. The Eagles were sure enough of themselves to declare that if it were not for their watch, then long ago Gondolin would have been discovered. They were sharp enough to see and even recognize individuals such as Hurin after his release from Angband. What happened to the Eagles that were keeping watch on the borders of Gondolin when Morgoth’s army arrived? I understand that Turgon and the Gondolindrim had been warned by the Valar via Ulmo’s message given to Tuor and that Maeglin betrayed the location of the city to Morgoth. However, once that message that the city was not long to last was delivered and Maeglin’s treason accomplished, were the Eagles released from their watch on Gondolin? If the Eagles were at the bidding of Manwë did he know that they were not going to be able to keep guard and that is why he sent Tuor? I guess I just don’t understand how one minute no spy of Angband can get near the place unnoticed and the next a whole army of orcs, dragons, and balrogs gets to the city walls without any warning

The Silmarillion is the only account of the fall of Gondolin that I have read so it may be that I just haven’t heard the whole story. Whatever the reason, I wondered if you could help.

–Joe Roark

A: Tough-sounding question, but ultimately it might be a bit simpler than it appears. In other questions about the Eagles, we’ve established that they were indeed Manwë’s special servants, interfering little in human affairs except at dire need and when no other help was available, giving rise to the ‘deus ex machina’ comparison. Well and good. Now, take for a moment this theory: Small parties or individuals wandering around, vaguely looking for Gondolin but not really sure where to start, compared to an army which had been given specific instructions from somebody who knew exactly where to go. Am I making sense yet? I thought not. My supposition is that as long as the location wasn’t really known, but only guessed, it was still within Manwë’s jurisdiction (or within the Eagles’ as his representatives) to help protect it by somehow distracting or waylaying the ones who were looking for it, and also keeping Morgoth’s eyes from penetrating the place. But if once somebody took an active interest in betraying the location, it was not for Manwë (or his Eagles), to be able to interfere. What could they do? Pick out the eyes of an entire army? They couldn’t remove the knowledge from the minds of the enemies as to where Gondolin was hidden. Once the location became known, it was too late, there was nothing the Eagles could do. It might also be argued that the betrayal of Gondolin was Fate, foretold by Ulmo who told Turgon not to get too attached to his toys, because one day a messenger would come and that would be the sign that the fall was at hand. Turgon decided to stay and fight. Well and good, but now we’re getting into a whole realm of Fate vs. Free Will that I can’t even begin to address in this space. But I firmly believe that the Eagles were not permitted to interfere too freely in the affairs of Elves and Men, and that once an action was done by Maeglin, it could not be undone or even reasonably counteracted by the Eagles.

– Anwyn

Q: Maglor was left singing by the shore where he cast the Silmaril. So really he should still be there, or did something else happen to him????

–Tim

A: Maglor’s fate is recorded in The Silmarillion as follows: “And it is told of Maglor that he could not endure the pain with which the Silmaril tormented him; and he cast it at last into the Sea, and thereafter he wandered ever upon the shores, singing in pain and regret beside the waves. For Maglor was mighty among the singers of old, named only after Daeron of Doriath; but he came never back among the people of the Elves.” (p. 254). In The Shaping of Middle-earth, Christopher Tolkien published a text of the “Annals of Beleriand”, and in a late addition to it, his father wrote “but Maithros perished and his Silmaril went into the bosom of the earth, and Maglor cast his into the sea, and wandered for ever on the shores of the world” (note 71, p. 313)

That’s really all that is recorded of his fate, and we can read into that whatever we please.

– Turgon

Q: Why were the Nazgûl so afraid of, or at least able to be harmed by, water?

Q: Why were the Nazgûl so afraid of, or at least able to be harmed by, water?

–Alex Hesser

Also

Q: Where can one find an account of the Witch-king of Angmar? I just finished The Silmarillion, but it glosses over the history of Arnor.

–Chris Nicholson

A: It is sometimes hard to find detailed information on the Nazgûl, or going by their elvish name, the Úlairi. You just need to know where to look. Pull out your copy of The Return of the King and read through those wonderful Appendices! The Professor wrote them for YOU, his faithful readers.

First look at Appendix A, Annals of the Kings and Rulers, Part I—”The Númenorean Kings,” and narrow it down to Sections (iii) and (iv). On page 320 begins an account of ‘The North-kingdom and the Dúnedain,’ which reveals fascinating details of the Men who were Aragorn’s ancestors and their strife with the Witch-king. On page 331 you’ll read of the climactic battle which joined Elves from the Grey Havens, a fleet of Men from Gondor, and skilled Hobbit archers from the Shire; all united in a last front against Angmar. Concise maps of the battle, which are very helpful, can be found in Karen Wynn Fonstad’s The Atlas of Middle-earth, pages 58-59.

As for the Nazgûl being harmed by water, I’m not certain that’s the case. Only magical blades laden with Elvish spells could do true harm to a Ringwraith. As Frodo attempted escape across the Ford of Bruinen, the Nine Riders were not afraid of the water itself… the Morgul-lord spurred his horse forward, the others following. Ordinary water would not hinder them but burning fire in the hands of an Elf-lord is a great deterrent! But remember Elrond commanded this river and it was certainly not ordinary; thus the brute force of his magic flood was strong enough to sweep them away.

– Quickbeam

Update!

Thanks to several readers who have a keen eye for Unfinished Tales. I would be remiss if I did not add more to my incomplete answer. Look in Part III—The Third Age, Section IV: “The Hunt for the Ring” wherein we learn from Christopher Tolkien that JRRT had drafted material about the Nazgûls’ fear of water but then finally made the concept less specific because it was problematic.

At the Ford of Bruinen only the Witch-king and two others, with the lure of the Ring straight before them, had dared to enter the river; the others were driven into it by Glorfindel and Aragorn.

and also:

My father nowhere explained the Ringwraiths’ fear of water… thus of the Rider seen on the far side of Bucklebury Ferry just after the Hobbits had crossed it is said that “he was well aware that the Ring had crossed the river; but the river was a barrier to his sense of its movement,” and that the Nazgûl would not touch the “Elvish” waters of the Branduin. But it is not made clear how they crossed other rivers that lay in their path, such as the Greyflood, where there was only “a dangerous ford formed by the ruins of the bridge.” My father did indeed note that the idea was difficult to sustain.

Here is what one reader had to say:

If you check out “The Hunt for the Ring” in Unfinished Tales, you will find a lot more about the Nazgûl’s fear of water (although it seems that ultimately Tolkien was going to give up the idea as being “difficult to maintain.”) Also, the idea of ghosts or spirits being unable to cross bodies of water is not an uncommon folk-tale motif. This section of Unfinished Tales has lots of good stuff on the Nazgûl, and the account of their arrival in Hobbiton the very day Frodo was setting out is absolutely fascinating (especially their encounters with Saruman, Wormtongue, and the “squint-eyed southerner” at Bree).

–Philip Covitz

Also on a separate note, some readers took issue with my point that “only magical blades laden with Elvish spells” could harm a Nazgûl. Consider the episode where Merry and Éowyn face the Lord of the Nazgûl and defeat him. One Hobbit using a Númenorean blade; one human woman using steel of the Mark. Neither are using Elvish blades yet they both seem to get the job done. This is true and sound logic, so let me modify my answer briefly: the most lethal implements against a Ringwraith would be those imbued with some greater skill or magic beyond common steel. Be it the magic of Elves or the high spirit of Númenor—it would be some component that upheld the legacy of Valinor and scorn for the works of Shadow. Merry had the proper instrument and delivered a blow breaking the spell of the Witch-king’s invulnerability. And Éowyn may have been wielding only a “regular sword” but the rules of the game had changed at that point. Éowyn’s role was to fulfill the prophecy, and being not a mortal man, she brought Fate full circle to the dreaded Morgul-lord.

Q: Why were the Orcs so easily able to spot Frodo’s body lying in the passage of Cirith Ungol when he was wrapped in his elven cloak? It was dark in the passage and even accepting that Orcs have good night/dark vision, would their night vision surpass the excellent day vision of the Men of Rohan who passed the Three Hunters in good light on the plains of Rohan?

Q: Why were the Orcs so easily able to spot Frodo’s body lying in the passage of Cirith Ungol when he was wrapped in his elven cloak? It was dark in the passage and even accepting that Orcs have good night/dark vision, would their night vision surpass the excellent day vision of the Men of Rohan who passed the Three Hunters in good light on the plains of Rohan?

–The Grey Pilgrim

A: Consider how watchful the Orcs were from high up in the Tower. Frodo was running around shouting, with Sam yelling behind him… and in the battle with Shelob the Phial of Galadriel was blasting elf-light in all directions. There’s not an Orc anywhere who would have missed the commotion! Shagrat indicates that his boys were full witness to the “lights and shouting and all.” They knew exactly where to look at the mouth of the Lair.

Also recall it wasn’t a large, exposed space. The area just past the webbed tunnel exit was only 600 feet across measuring to the steps of the Cleft, maybe less. Where the two Orc troops converged, they found Frodo “Lying right in the road.” Maybe they didn’t see him right away, but with dozens of Orcs tramping about looking for further evidence in an enclosed space, they likely stumbled right over him.

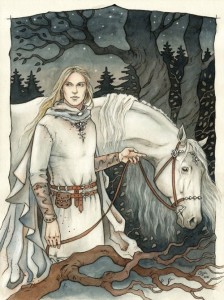

Q: Legolas and Gandalf (on Shadowfax) rode “elf-fashion” (without saddle or bridle), yet when Glorfindel lets Frodo ride his horse at the Ford, he “shortens the stirrups up to the saddle skirts”. The best I can figure is that since Glorfindel was riding to seek out Frodo and help him (possibly by fighting the Nazgûl) he rode out equipped for battle, and a saddle and bridle would make reasonable sense in that case. What are your opinions?

Q: Legolas and Gandalf (on Shadowfax) rode “elf-fashion” (without saddle or bridle), yet when Glorfindel lets Frodo ride his horse at the Ford, he “shortens the stirrups up to the saddle skirts”. The best I can figure is that since Glorfindel was riding to seek out Frodo and help him (possibly by fighting the Nazgûl) he rode out equipped for battle, and a saddle and bridle would make reasonable sense in that case. What are your opinions?

–Ed Bauza

A: In The Fellowship of the Ring, the first appearance of Glorfindel on the road is described as follows: “Suddenly into view below came a white horse, gleaming in the shadows, running swiftly. In the dusk its bit and bridle flickered and flashed, as if it were studded with gems like living stars.” (page 221 of the first edition, 1954)

Later, Glorfindel tells Frodo: “You shall ride my horse. I will shorten the stirrups up to the saddle-skirts” (page 223).

In 1958, a reader of The Lord of the Rings asked Tolkien the following question: “Why is Glorfindel’s horse described as having a ‘bridle and bit’ when Elves ride without bit, bridle or saddle?”

Tolkien’s answer was as follows: “I could, I suppose, answer: ‘a trick-cyclist can ride a bicycle with handle-bars!’ But actually bridle was casually and carelessly used for what I suppose should have been called a headstall. Or rather, since bit was added (I 221) long ago (Chapter I 12 was written very early) I had not considered the natural ways of elves with animals. Glorfindel’s horse would have an ornamental headstall, carrying a plume, and with the straps studded with jewels and small bells; but Glor. would certainly not use a bit. I will change bridle and bit to headstall.” (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, page 279)

In the second edition of The Fellowship of the Ring, the reading of “bridle and bit” was changed to “headstall” on page 221, but the reading on page 223 remains the same as in the original edition. So, for whatever reason, Glorfindel must have been riding with a saddle, even though that is not normally elf-fashion.

– Turgon

Q: If Frodo was a little hobbit, how did the Ring always stay on his finger and never fall off? That goes for Bilbo too.

Q: If Frodo was a little hobbit, how did the Ring always stay on his finger and never fall off? That goes for Bilbo too.

–Alex Hesser

A: The Ring had strange powers that we aren’t fully informed of, but one of the powers that we *are* told about was the ability to change its size. Gandalf is speaking to Frodo about the Ring: “Though he had found out that the thing needed looking after; it did not seem always of the same size or weight; it shrank or expanded in an odd way, and might suddenly slip off a finger where it had been tight.” “Yes, he warned me of that in his last letter,” said Frodo, “so I have always kept it on its chain.” So that answers both questions: the Ring stayed on the finger if it was pleased to do so. You may remember also in The Hobbit how when Bilbo thought he was wearing the Ring, it suddenly wasn’t on his finger and he was seen by goblins. Also, there is the fact that Frodo never wore it much, and kept it on its chain, as he said.

– Anwyn

Q: I have forgotten what became of the Seven Rings for the Dwarven lords. I am sure the answer to this question is fairly easy, but it has been quite a while since I really studied the books and I guess I have just gotten lazy.

Q: I have forgotten what became of the Seven Rings for the Dwarven lords. I am sure the answer to this question is fairly easy, but it has been quite a while since I really studied the books and I guess I have just gotten lazy.

–Jeremy Danford

A: When Gandalf entered Dol Guldur in 2845 (Third Age) and found Thrain imprisoned there, Thrain complained that “the last of the Seven” had been taken from him. The Rings of Power were forged in the middle of the Second Age. The ring that was possessed by Thrain was believed to have been the first of the Seven that was forged, and it was said that it was given to the King of Khazad-dum, Durin III. The possessors did not display their rings, nor speak of them, and the histories of the Dwarves do not detail the fate of each of the Seven. In “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age”, a section published in The Silmarillion, it is written that the Dwarves “used their rings only for the getting of wealth; but wrath and an overmastering greed of gold were kindled in their hearts, of which evil enough after came to the profit of Sauron. It is said that the foundation of each of the Seven Hoards of the Dwarf-kings of old was a golden ring; but all those hoards long ago were plundered and the Dragons devoured them, and of the Seven Rings some were consumed in fire and some Sauron recovered.” (pages 288-289)

– Turgon

Update!

Rallas has written in with the following interesting comment: “Remember that in the text preceding the Council of Elrond where Frodo and Gimli are talking, Frodo asks what has brought the Dwarf so far from the Lonely Mountain, Gimli winks but defers further conversation till later. During the council he states that the messengers from the South had come a number of times to offer great wealth and precious things for information about Bilbo. In the “History of Middle-Earth” Tolkien’s writings clearly state that the precious things which were offered if the Dwarves could obtain the ‘trifle’ from Bilbo would be three rings as their forefathers had had of old. Sauron must have had at least three of the Dwarven rings in his possession.”

– Turgon

Update to the Update

Reader “Ban” brought up a good point about Rallas’s comment: “Pardon my nit-pickiness, but wasn’t it Gloin that Frodo was talking to before the Council? Gimli wasn’t introduced as Gloin’s son until everybody was introduced by Elrond.” Ban is absolutely correct–it was Gloin!

– Turgon

Q: Why did Tolkien mention stars so much? I’ve heard that he had a love of astronomy, but there seems to be more in his mentioning of stars in almost all of his books than just his hobby. There seems to be some sort of symbolism in connecting the stars to the elves, but I just can’t seem to figure it out! Does anyone over at the Green Books or any other fan have any idea what stars are supposed to symbolize?

–The Dodger

A: Tolkien clearly had an immense love of the natural world, from flora and fauna to the orbs in the sky. In one sense, his entire mythology of Middle-earth is based upon looking at the natural world and presenting new “myths’ for why things are the way they are. His mythology began in the teens with a question of the meaning of a word in an Anglo-Saxon religious poem, “Crist” by Cynewulf: “Eala Earendel engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum sended”. In English: “Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, above the middle-earth sent unto men.” Tolkien viewed that the word ‘Earendel’ had originally been a name for the evening star, or Venus, and Tolkien created the myth of Earendil, who sailed the heavens in a ship, bearing a Silmaril. The Silmarillion also contains Tolkien’s wonderful story of the creation of the Sun and the Moon from the last fruits of the Two Trees of Valinor. And the stars themselves were kindled by the Vala Varda, who was the spouse of Manwe and who was especially concerned with light. (Varda filled the lamps of the Valar with light, and set the courses in the sky of the Sun and Moon.) Varda was especially revered by the Elves, who first awoke in Middle-earth in the vale of Cuivienen, under the starlight of Varda. She was usually called Elbereth (Sindarin, ‘star-queen’). And that is basis of the internal symbolism connecting the Elves and the stars.

– Turgon

Update!

A reader (“VLT”) wrote in with some interesting observations: “There might be another simple reason why stars get so often mentioned in Tolkien’s books. In the past – especially for travellers – stars played very important role: they were used for orientation at night, to determine cardinal points, to tell the time…. Their movements announced seasonal changes (Nile´s flooding). Their behaviour and appearance were base for many myths, stories and tales, often of symbolical meaning. To sum it up, stars had much greater importance and significance in people´s lives in the past and this might be reflected in the books.”

– Turgon

Q: Where did Ungoliant come from?

Q: Where did Ungoliant come from?

–Alex Hesser

A: The most information we get out of Tolkien concerning Ungoliant’s origins is found in The Silmarillion: “There, beneath the sheer walls of the mountains and the cold dark sea, the shadows were deepest and thickest in the world; and there in Avathar, secret and unknown, Ungoliant had made her abode. The Eldar knew not whence she came; but some have said that in ages long before she descended from the darkness that lies about Arda, when Melkor first looked down in envy upon the Kingdom of Manwë, and that in the beginning she was one of those that he corrupted to his service.” This tells me that she was likely a Maiar, who, like Sauron, was corrupted by Melkor. It goes on to say, however, that she soon ceased to serve Melkor, serving only herself and her great hunger, devouring everything she could eat, even light itself.

– Anwyn