Once again it has been a long time since I posted in this series, but what with the run-up to The Hobbit: An Unexpected Adventure and the reaction to it, TheOneRing.net has been a busy place, and now we’re coming up on The One Expected Party on Oscar night! But I’ll delay no longer.

In the first entry I recalled getting the permission to interview the filmmakers and going down to start my work, back in September-October of 2003. The second one dealt with my first interview and tours of the Three Foot Six office building and the Stone Street Studios. Now, more of the facilities I visited.

The Film Unit

My third full day in Wellington was Wednesday, October 1. Melissa Booth called and said I could come to the new Film Unit building to meet Barrie Osborne. He, as I cannot stress often enough, was the one responsible for getting me New Line’s permission to interview the filmmakers for my book. This meeting, though, wouldn’t be for an interview. (I interviewed Barrie twice for the book, first a couple of weeks later and again during my third Wellington visit in December, 2004.) He was driving out to the old Film Unit facility that afternoon to give the people working there, sound mixers, editors, and other post-production crew members, a pep talk.

My third full day in Wellington was Wednesday, October 1. Melissa Booth called and said I could come to the new Film Unit building to meet Barrie Osborne. He, as I cannot stress often enough, was the one responsible for getting me New Line’s permission to interview the filmmakers for my book. This meeting, though, wouldn’t be for an interview. (I interviewed Barrie twice for the book, first a couple of weeks later and again during my third Wellington visit in December, 2004.) He was driving out to the old Film Unit facility that afternoon to give the people working there, sound mixers, editors, and other post-production crew members, a pep talk.

As most readers know, the race to finish The Return of the King was on by that point, and a lot of people were working long hours. I was told that Barrie often gave these pep talks, and the filmmakers really appreciated them; it was part of what gave the production that feeling of being one big family. I could at least introduce myself to Barrie and ride with him to the Film Unit; the half-hour drives there and back would allow us time to talk about my project.

The Film Unit was a government-owned post-production facility that Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh bought in 1998 to keep it from being sold and probably closed down. As the only post-production house on that scale in New Zealand, it was vital to making LotR. When I arrived, the new Film Unit building (now Park Road Post) was being built in Miramar, a few blocks from the Weta building in one direction and the Stone Street Studios in the other. An old building that would eventually be replaced was still acting as a reception area (above, right). The three new sound-editing rooms that can be seen in the RotK supplement “The End of All Things” had been completed, as had some offices and a long corridor to the left as one entered the building.

I met Barrie in one of those offices, that of Rosemary Dority (left), familiar to fans of the supplements as the Post Production Supervisor of LotR. She was incredibly friendly and let me stash all the stuff I had to lug around behind her desk when I was in the building. Barrie used her office when he had meetings in the new Film Unit.

Barrie was wolfing down lunch, a sandwich, at about 2:30 in the afternoon before heading for Lower Hutt. As we headed out he gave me a quick tour of the new sound-editing rooms. I met Christopher Boyce and saw my first (unfinished) footage from RotK. It was a scene of Frodo, Sam, and Gollum in a desolate landscape, I think from their first scene in the film, before they get to Ithilien.

Barrie was wolfing down lunch, a sandwich, at about 2:30 in the afternoon before heading for Lower Hutt. As we headed out he gave me a quick tour of the new sound-editing rooms. I met Christopher Boyce and saw my first (unfinished) footage from RotK. It was a scene of Frodo, Sam, and Gollum in a desolate landscape, I think from their first scene in the film, before they get to Ithilien.

Then Barrie and I were off to the old Film Unit. Once inside, we entered a small auditorium where many members of the post-production team were gathered. Barrie thanked them all for their hard work and sprang a surprise on all of us. He was going to show us a brand-new 35mm copy of the first RotK trailer. Coincidentally, that trailer had premiered in American theaters the day I left for Wellington, so I hadn’t seen it.

More importantly, the team in that room hadn’t seen any finished footage from the film, despite having worked on it for so long. The trailer started on the big screen. You probably remember that trailer, which basically ended with you thinking, “I want to see that film, and I want to see it NOW!” The room went crazy, with people cheering and some even crying. It was an amazing moment and gave me a vivid sense of how dedicated these people were to this huge film project.

Afterwards Barrie introduced me to Sue Thompson, CEO of The Film Unit, who still had tears in her eyes. She agreed to let me interview her. My only other visit to the old Film Unit facility was two weeks later, on October 15, when I talked to her and then immediately afterward to costume designer Ngila Dickson.

I’ve looked for a photo of that building online, but no one ever seems to have been tempted to take a picture of it. It was austere, bland, and, as Peter described it to me when I later interviewed him, “a very government sort of ‘Soviet bloc’ feeling place.” It was already clear, however, that the new Film Unit in Miramar, in contrast, would be modern and gorgeous.

The PostHouse

On October 1, when Barrie and I returned to the new Film Unit building, I met Peter Doyle, the Supervising Digital Colorist for LotR (and many other films thereafter, including King Kong and six of the Harry Potter films). He agreed to let me come to The PostHouse the next day. It was housed in a warehouse across the street from the new Film Unit.

Peter had helped invent a new digital process called selective digital grading specifically for LotR. It allows a colorist to change the visual qualities (altering colors and changing light levels) for individual portions of a shot without changing the other portions. It was a revolutionary technology and has been adopted almost universally in the international film industry.

Unfortunately I had no idea that I was going to have this opportunity to talk with Peter, so I wasn’t prepared to interview him. Indeed, at that point there wasn’t much information on the new technique available. But Peter took me into a big dark room where dozens of experts were working at rows of computers, grading shots from the film. We sat down at a monitor, and he very generously gave me a 25-minute demonstration of how selective digital grading is done.

He used two main examples: a close-up of Denethor’s face and the distant view of Gandalf’s cart going along a road between some fields on the way to the Grey Havens. The tiny tweaks he was able to make on very limited parts of the image were wonderful. He could dial up a brighter patch of sunlight in one of the fields in the cart shot, subtly changing the tone of the image. It’s a beautiful process to watch, and even though I have very limited computer expertise, I thought it would be a very rewarding thing to do.

He used two main examples: a close-up of Denethor’s face and the distant view of Gandalf’s cart going along a road between some fields on the way to the Grey Havens. The tiny tweaks he was able to make on very limited parts of the image were wonderful. He could dial up a brighter patch of sunlight in one of the fields in the cart shot, subtly changing the tone of the image. It’s a beautiful process to watch, and even though I have very limited computer expertise, I thought it would be a very rewarding thing to do.

Peter can be seen at work in the all-too-brief supplement “Digital Grading” on the Fellowship of the Ring extended DVD/Blu-ray (right, with cinematographer Andrew Lesnie looking on). I think it’s a pity that none of the other supplements dealt with this technique.

Weta Workshop and Digital

About a week into my visit, on Tuesday, October 7, I went to the Weta Ltd. building for the first time for an interview with Richard Taylor. In order to get in, I was handed the only legal document I ever ended up signing during the whole project: an agreement not to bring a camera into Weta Workshop. I could see why. There were design drawings and models all over the place. Naturally I signed, since, as I’ve pointed out in previous entries, I wasn’t able to take photographs inside any of the filmmaking facilities. Hence the fact that most of my illustrations for this series either show the outsides of buildings or are frames from the DVD supplements.

Richard is absolutely as nice as he seems in the many interviews he has done over the years. To my surprise, he had invited two of his top designers, Daniel Falconer and Ben Wooten, to join us. It was a terrific interview, and we talked for about 85 minutes.

Afterward Daniel gave me a tour of Weta Workshop. Of course there were displays of all sorts of models and designs, including early conception images of Gollum. We saw the forge area, where the swords and other metal items are made. At one point we were in a big studio where the full-size version of the upper half of Treebeard was standing. That’s the one where Billy Boyd and Dominic Monaghan could actually sit on his hands.

Afterward Daniel gave me a tour of Weta Workshop. Of course there were displays of all sorts of models and designs, including early conception images of Gollum. We saw the forge area, where the swords and other metal items are made. At one point we were in a big studio where the full-size version of the upper half of Treebeard was standing. That’s the one where Billy Boyd and Dominic Monaghan could actually sit on his hands.

I had read somewhere that there was a big snail, native to New Zealand, stuck in Treebeard’s twiggy beard. Sure enough, there it was. I commented to Daniel that I had known about the snail but, try as I might, during screenings I was never able to spot it. He replied, “Neither can I—and I put it there!” (That was another of those moments when it really struck me that I was right there in Wellington, talking to people who were still making LotR. How in the world had I actually gotten there?!)

Afterwards, as I left Weta Workshop, through an open door I spotted the giant model of the three trolls, turned to stone, which I had earlier seen inside the studio near Treebeard. Since they were visible from the public sidewalk, I allowed myself to take out a camera and photograph them (left). I trust that was not a violation of the legal agreement I had signed.

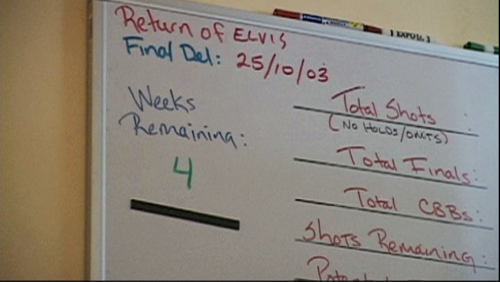

About two weeks later, Barrie suggested that I interview Matt Aitken of Weta Digital. Matt is another face familiar to fans as a talking head in the supplements (right). He’s in charge of scanning models for the digital effects. He didn’t work at the main Weta Digital headquarters on Manuka Street but at another facility further south on the Miramar peninsula. When I entered the building, I saw a bulletin board on the wall, with the number of shots remaining to have special-effects added. It was a reminder of the race to finish the film (again, documented in “The End of All Things,” see below).

About two weeks later, Barrie suggested that I interview Matt Aitken of Weta Digital. Matt is another face familiar to fans as a talking head in the supplements (right). He’s in charge of scanning models for the digital effects. He didn’t work at the main Weta Digital headquarters on Manuka Street but at another facility further south on the Miramar peninsula. When I entered the building, I saw a bulletin board on the wall, with the number of shots remaining to have special-effects added. It was a reminder of the race to finish the film (again, documented in “The End of All Things,” see below).

Matt gave me a lot of specific information on the build-up of computing power at Weta, which grew hugely between The Frighteners and the end of the work on RotK. After that appointment, someone was supposed to pick me up and drive me to Manuka Street for a tour of the main Weta facility. Unfortunately, that person apparently never got the word. So Matt, busy though he was, drove me over himself and showed me around.

There was a big room full of animators working on various scenes, with full suits of the Elvish armor from the prologue of FotR hanging on the walls above them. (Another one hung on a stand just inside the main Manuka Street entrance. I must say I coveted that armor.) There was a series of rooms full of racks of 3000 hard drives laboring away at rendering and other tasks, accompanied by the roar of huge air-conditioning units. I also was introduced to the heart of the whole enterprise: the surprisingly small scanning room. There on one side were three big machines, all named after dragons and all scanning negatives straight out of the camera into digital files, to be color graded and to have their special effects done, among other procedures. On the other side of the room were two ArriLaser scanners putting the resulting frames back onto raw negative film. Back in the 1990s it took 45 seconds per frame to do that. By 2003 it took more like 2.5 seconds. Peter reportedly would not OK any special-effects shot until he saw it projected on a screen in 35mm, so there was a lot of footage to be scanned back onto negative film.

The Miniatures Unit

For some reason, on my first visit, I never asked to tour the miniatures department. I guess I was too busy. On my second visit, in June, 2004, I requested permission through Peter Jackson’s assistant, but was told I couldn’t see it. By that time, King Kong was well into production, and the facility was full of miniatures for that film. Secret stuff.

I interviewed Peter himself on the last day of that second visit. In December I returned and tried again, asking Peter’s assistant if he could get me permission to tour the miniatures department. Five minutes later I was given the name of a person to call and set up an appointment. I assume my interview with Peter reassured him that I was a serious and trustworthy person.

When I arrived at the miniatures unit, in yet another big building somewhere on the Miramar Peninsula, two other people and I got a tour from a pleasant young man who showed us such things as the model of the King Kong ship and lots of tiny jungles. Afterwards I went in to thank the woman who had arranged the appointment for me. She asked if I wanted to talk to Alex.

The name Alex didn’t ring a bell at that moment, I must admit. Still, I was willing to talk to anyone who was willing to talk to me, so I said yes. Luckily I had brought my recorder along. I was ushered into a conference room, and a few minutes later in walked Alex Funke. Oh, that Alex, the one who had worked on groundbreaking digital effects films such as The Abyss, Total Recall, and Starship Troopers. The Visual Effects Director of Photography for the miniatures unit and winner of two Oscars for LotR. (He’s now the motion-control supervisor for The Hobbit. That’s the technique that allows different elements of the same shot to be filmed at different times and/or places and joined smoothly together.)

That was the only interview I ever went into absolutely cold, with no advance notice or preparation. Fortunately Alex was a pro at interviews and basically just launched in, with me interjecting the occasional question. Apart from the technical information he gave me, he also conveyed a powerful sense of how congenial a working environment Peter had built up for his employees. Alex has enormous respect for the decent way in which people are treated. He himself, though having worked for years in the Hollywood film industry, had moved permanently to New Zealand to work with Peter—as Joe Letteri and others have.

Overall, the facilities built up for LotR make up the equivalent of a big Hollywood studio back in the golden days of the industry. A major, special-effects-heavy film can be made there, from script to screen. I feel enormously privileged to have seen so much of it.

We’ll encounter these places again in future entries.