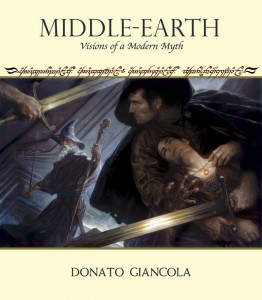

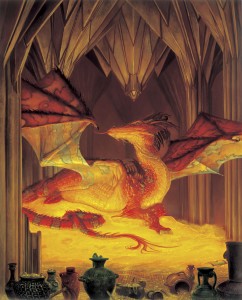

Donato Giancola’s artwork will be familiar to many readers of TORn. His paintings have been used as the covers for many books, including the Science Fiction Book Club’s combined edition of The Lord of the Rings. Recently, he published a volume which brings together many of his Middle Earth depictions. If you haven’t yet seen Giancola’s gorgeous book Middle Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth, then you’ve missed a treat. Crammed with beautiful prints of his paintings and sketches inspired by Tolkien’s writing, the book includes fascinating comments and up close images of details from Giancola’s amazing pictures. It’s a great opportunity to see Middle Earth afresh; we know so well the images from the movies or from John Howe and Alan Lee (amongst others); but here we find well known characters and places reimagined. Giancola’s focus tends to be on faces, and he brilliantly brings to life the anguish or ecstasy of a moment as seen in a character’s eyes. His drawings of anatomy are like ancient Greek sculptures, with every muscle seen as, for example, Gollum struggles against Sam and Frodo in Emyn Muil. I especially love his ‘The Great Dragon Smaug’ and ‘Eowyn and the Lord of the Nazgul’. Ted Nasmith wrote the foreword for Visions of a Modern Myth; he writes of Giancola, ‘His art is exactingly and lovingly rendered with consummate skill, yet the end result is typically relaxed and very pleasant to the eye – no easy feat!’

Donato Giancola’s artwork will be familiar to many readers of TORn. His paintings have been used as the covers for many books, including the Science Fiction Book Club’s combined edition of The Lord of the Rings. Recently, he published a volume which brings together many of his Middle Earth depictions. If you haven’t yet seen Giancola’s gorgeous book Middle Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth, then you’ve missed a treat. Crammed with beautiful prints of his paintings and sketches inspired by Tolkien’s writing, the book includes fascinating comments and up close images of details from Giancola’s amazing pictures. It’s a great opportunity to see Middle Earth afresh; we know so well the images from the movies or from John Howe and Alan Lee (amongst others); but here we find well known characters and places reimagined. Giancola’s focus tends to be on faces, and he brilliantly brings to life the anguish or ecstasy of a moment as seen in a character’s eyes. His drawings of anatomy are like ancient Greek sculptures, with every muscle seen as, for example, Gollum struggles against Sam and Frodo in Emyn Muil. I especially love his ‘The Great Dragon Smaug’ and ‘Eowyn and the Lord of the Nazgul’. Ted Nasmith wrote the foreword for Visions of a Modern Myth; he writes of Giancola, ‘His art is exactingly and lovingly rendered with consummate skill, yet the end result is typically relaxed and very pleasant to the eye – no easy feat!’

Donato is a good friend to TheOneRing.net, and he was recently interviewed by another good friend of ours, George Beahm – writer of books such as The Essential J.R.R. Tolkien Sourcebook (with Colleen Doran) and Kirk’s Works (with George Barr, on the artwork of Tim Kirk). Beahm’s interview appears below. I hope it wets your appetite to see more of the stunning art of Donato Giancola.

Donato Giancola: Drawn to Middle-earth

(an interview conducted by George Beahm)

“The goal of a passionate artist is to try and make a masterpiece each and every time, yet be wise enough to know you will fall short.”

— Donato Giancola

This interview with Donato Giancola was conducted at Illuxcon 3 in November 2010.

Drawn to Art

Hoarse from talking nonstop–at lectures, demonstrations, and in conversations with fantasy fans at the third Illuxcon in Altoona, Pennsylvania–Donato Giancola takes advantage of a quiet moment to do what he does best: create art. He seats himself with an art book in hand and opens to a page with a drawing of Red Sonja, to resume where he left off. He draws carefully and methodically, adding more detail.

Behind him is an exhibit of his original art, drawn from Middle-earth: Visions of a Modern Myth. There are dozens of pieces, oil paintings and toned drawings in varying sizes that command one’s attention and invite closer examination. All are rendered in a readily recognizable style: dynamically composed, exquisitely drawn, always memorable and often haunting, portraits of people in expressive poses.

The book

Donato’s latest book was years in the making.

Donato’s latest book was years in the making.

“Tim Underwood and Arnie Fenner have been wanting to do an art book with me for years,” said Donato. “They finally pitched this idea.’What about a Middle-earth book?’ I jumped on it; they knew which button to push. As I began to compile the art for the book, I felt there were voids in the stories and the characters that had not been tackled for me, it was daunting to think that I had just four months to create new art and put it all together. I turned to drawings as a way to fill out the volume of the book, to slow its pacing, and put more power and weight into the color images.

“It turned out to be a wonderful way to design the book, presenting the art in a way that alternated color paintings with drawings.”

The finished book, measuring approximately 9 x 12 inches, is 80 pages that encompass dozens of pieces, many done especially for this project. It is the culmination of a personal and professional dream for Donato, to finally collect his visions of Tolkien’s world in a single volume.

Drawn to Tolkien

Donato’s first journey to Middle-earth took place many years ago when his brother Michael handed him a paperback copy of The Hobbit and said, “You might like to read this.”

Donato’s first journey to Middle-earth took place many years ago when his brother Michael handed him a paperback copy of The Hobbit and said, “You might like to read this.”

Donato was then thirteen-years-old.

Michael could not have picked a better book to fire his brother’s imagination. Published in 1937, The Hobbit drew high praise by reviewers, including the Times Literary Supplement. “Its place is with Alice, Flatland, Phantastes, The Wind in the Willows…[The] prediction is dangerous: but The Hobbit may well prove a classic.” The prescient review was from Tolkien’s fellow author and friend, C.S. Lewis.

The reading of The Hobbit proved to be a life-changing experience for Donato, who found in Tolkien’s mythic fantasy a world so painstakingly conceived that he, like countless other creators–artists, musicians, poets, writers, sculptors–happily succumbed to its enduring enchantment.

“Tolkien is one of the first books I read purely for love of enjoying literature,” he recalls. “It was the foundation of how I perceived what a novel is. It was reading for the sheer pleasure and enjoyment of immersing oneself in a fantastic world.”

Over the next weeks, Donato went to the bookstore to purchase three paperbacks that comprised the separate volumes of The Lord of the Rings, with cover art by Darrel Sweet. (Note: on a wall at Donato’s home is the original Sweet cover painting for The Hobbit.)

“I still have those well-loved copies in the studio today,” says Donato. “The most enjoyable aspect of reading those novels was the incredibly rich history of the cultures Tolkien provided.”

Donato continued his journey through Middle-earth at the local library. “I was thrilled to discover The Lost Tales, Unfinished Tales, and The Silmarillion. I spent many afternoons there, immersed in the world of Middle-earth.”

For Donato, as it has been for other fantasy illustrators, The Lord of the Rings is the gold standard in epic fantasy against which all such books are measured. “When I’m reading modern fantasy, it’s always in comparison to what Tolkien did; the depth of creation, the depth of his characters and their complexities, and the histories.”

Reflecting life, the characters in The Lord of the Rings are fraught with human frailty: dwarves, hobbits, wizards or men, all are imperfect beings struggling with their consciences. As such, they ring true as fictional characters because we see ourselves, in part or in whole, in them. We, too, are flawed, unlike Aragorn, whose character is flawless.

“I think the only one who could be seen as perfect is Aragorn. He doesn’t seem to have any faults. But everyone else has an ingrained weakness to his character that needs mending or healing, developing or nurturing. When I reflect on these characters, they speak to me. Even though they’re wizards, elves or hobbits, they’re still people.”

When asked who among all the characters is his favorite, Donato quickly cites Boromir. “I’m drawn to him,” Donato admits. “I think of him as the middle seaman on Tolkien’s characters because he’s got a fatal flaw, a weakness. Maybe his desires made him more susceptible to the powers of The Ring, but he was the one who succumbed most to the temptation of what The Ring represented. He was also the one who gave up his life defending it.”

When asked who among all the characters is his favorite, Donato quickly cites Boromir. “I’m drawn to him,” Donato admits. “I think of him as the middle seaman on Tolkien’s characters because he’s got a fatal flaw, a weakness. Maybe his desires made him more susceptible to the powers of The Ring, but he was the one who succumbed most to the temptation of what The Ring represented. He was also the one who gave up his life defending it.”

On page 21 of Donato’s art book, one will find a revealing portrait of Boromir that shows his nobility but also hints at his eventual doom. Boromir has a look of sadness, of resignation, of doomed fate. “It is easy to characterize Boromir as simple and headstrong, but here he is depicted as a proud man conflicted by his duties as son, royal protector and royal emissary. Possessing great courage, he lacked the inherent wisdom of Westernesse which ran truer in his brother Faramir. Although never a villain, Boromir was one of Tolkien’s most human characters, constantly at battle between duty and morality. He is a figure of Shakespearean tragedy,” Donato wrote.

When asked to elaborate on that, Donato added, “Boromir, foreshadowing Frodo’s temptation, found it hard, and in the end, impossible to resist the One Ring. Frodo’s temptation becomes overwhelming in his weakened state, from his sheer persistence in bearing the ring. Boromir’s intentions were good. He sought not to empower himself, to make himself the king, but to save the kingdom–a totally selfless act. That’s why I find him so noble a character; he acted on that impulse even though it led to his doom.”

The Hobbit

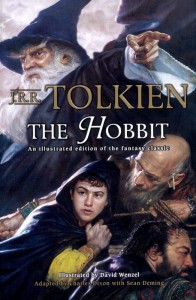

Given that The Hobbit was Donato’s first exposure to Tolkien’s world, it seems fitting that one of his first professional Tolkien assignments was to paint a cover to The Hobbit, a graphic novel adaptation drawn by David Wenzel.

Years later, David returned the favor by writing an essay for Donato’s book. In the essay, David praised Donato’s imagination and technical virtuosity: “Each dwarf was painted brilliantly, of course, but what struck me were the details. The tattooing, hair braiding and the jewelry he painted on each dwarf gave them a unique and distinctive presence that went beyond the written words. Each of Donato’s Tolkien works embodies aspects of this same attention to translation and detail.”

The original Hobbit painting, measuring 68 by 38 inches, is mounted on a weathered brick wall in Donato’s living room. By virtue of its size and visual presence, it dominates its wall. No smaller-sized reproduction can do it adequate justice; to fully appreciate its visual impact, one must see it in the original, just as the artist intended.

Titled “The Hobbit: Expulsion,” Gandalf towers over the dwarves and Bilbo, who seek shelter during their passage through the Misty Mountains; in the background, Mountain Giants throw massive boulders during a tempestuous storm. Significantly and symbolically, Gandalf is pointing the way. “In this painting,” writes Donato, “Bilbo’s semi-willing journey from his paradisical Shire, driven by curiosity, finds a parallel in the expulsion of Adam and Eve.”

Titled “The Hobbit: Expulsion,” Gandalf towers over the dwarves and Bilbo, who seek shelter during their passage through the Misty Mountains; in the background, Mountain Giants throw massive boulders during a tempestuous storm. Significantly and symbolically, Gandalf is pointing the way. “In this painting,” writes Donato, “Bilbo’s semi-willing journey from his paradisical Shire, driven by curiosity, finds a parallel in the expulsion of Adam and Eve.”

At this point in the story, Bilbo Baggins has yet to find what appears to be a simple gold ring, but in fact is the One Ring. Drawn far away from the comforts of home and hearth, Bilbo’s errant discovery of the One Ring is fraught with biblical symbology.

“Every encounter in The Hobbit,” writes Donato, “makes this world ever larger and more complex for the provincial young man. Bilbo’s humble and naive nature keeps him alive through his adventures, yet he is changed forever by his experience in the outside world. Unlike Adam and Eve, Bilbo physically returns to his Eden, but he never again feels genuinely home in it.”

When asked about how he approached illustrating this particular scene, Donato explains, “I immediately went to Peter Paul Rubens. What would he do here, and how would he connect with these people and convey their sensibilities of that moment? That timelessness, that old-world ‘feel’ was intentional. I like the sensibility, the design, the dynamic action that Rubens would bring. I intentionally masked their costuming, so you can’t see them clearly except for their faces and hands. What you see is movement through the composition. I tried to simplify it and remove as many visual cliches as possible.

When asked about how he approached illustrating this particular scene, Donato explains, “I immediately went to Peter Paul Rubens. What would he do here, and how would he connect with these people and convey their sensibilities of that moment? That timelessness, that old-world ‘feel’ was intentional. I like the sensibility, the design, the dynamic action that Rubens would bring. I intentionally masked their costuming, so you can’t see them clearly except for their faces and hands. What you see is movement through the composition. I tried to simplify it and remove as many visual cliches as possible.

“That’s what I try to do with so much of my work: to distill the information down to the core essence of people.”

It explains why he chose to forgo the more obvious scenes to illustrate. “The troll encounter, the goblin king under the mountain, the wargs chasing them off into the trees later set aflame by goblins, the Battle of the Five Armies, Smaug breathing fire … these are all climactic moments from chapter to chapter, but they don’t convey who was in the book, nor what the book is really about.”

The Lord of the Rings

The discovery of the One Ring sets off a chain of events that eventually place all inhabitants of Middle-earth in mortal jeopardy because its true master and creator, Sauron, seeks to wield it as the ultimate weapon. With it, he can extend his dominion well beyond Mordor to encompass all of Middle-earth–unless the reluctant hero, an extraordinarily brave hobbit named Frodo Baggins, can stop him, even at the cost of his own life. Mirroring Bilbo’s journey, Frodo’s journey is similarly perilous. “I will take the ring, though I do not know the way,” Frodo declares at the council of Elrond, where his traveling companions, the fellowship of the ring, is formed.

The discovery of the One Ring sets off a chain of events that eventually place all inhabitants of Middle-earth in mortal jeopardy because its true master and creator, Sauron, seeks to wield it as the ultimate weapon. With it, he can extend his dominion well beyond Mordor to encompass all of Middle-earth–unless the reluctant hero, an extraordinarily brave hobbit named Frodo Baggins, can stop him, even at the cost of his own life. Mirroring Bilbo’s journey, Frodo’s journey is similarly perilous. “I will take the ring, though I do not know the way,” Frodo declares at the council of Elrond, where his traveling companions, the fellowship of the ring, is formed.

For the Science Fiction Book Club edition of The Lord of the Rings, Donato visually acknowledges the epic scope of the story by painting an illustration measuring 55 x 33 inches: Deep in the bowels of the Earth, at Balin’s Tomb in Moria, Aragorn shelters Frodo, who has been stabbed with a spear by “a huge orc-chieftain, almost man-high, clad in black mail from head to foot,” wrote Tolkien.

As Donato explains, “The physical battle in Balin’s Tomb in Moria, however, is secondary to the psychological conflict over the Ring. Frodo struggles as much within himself as he does with external forces. Here he is depicted as a weary and defeated figure, his hand reaching out to the highlighted ring while another dark, groping hand echoes his gesture.”

As with his painting for The Hobbit, Donato sought to distill the information down to the core essence of people. “Do you illustrate the Balrog, the black riders chasing Frodo at the ford, the battle of Isengard, or the Pellenor fields?”

Donato, instead, chose the road less traveled: “Aragorn picking up Frodo, who was stabbed in the mines of Moria. Where’s the action in that? For me, that’s what the whole story is about.”

Commenting on both paintings, Donato said, “They’re both really non-climactic moments in the books, moments of passing that, when you’re reading, blow by very quickly. But I find that, as an artist, those are the moments that offer a wonderful opportunity to convey more of the true nature of the individuals and their characters.”

Illustrating Tolkien

“Creating a painting from the worlds of Middle-earth means you will be placed under the most intense scrutiny when it comes to details and accuracy,” Donato writes. “The admirers of Tolkien know no mercy when it comes to deviations and inaccuracies, myself included! I know those books inside and out, but still found myself making a few mistakes. I now run my sketches past my friends as a double check to catch any errors. Luckily, Tolkien provided artists with large loopholes for illustrating his novels–there’s very little physical description of either characters or places. His descriptions are generally emotional and, for that reason, resonate with the reader more than the offerings of other authors. This is what I love regarding the works; there’s a strong emotional foundation upon which to build a very broad range of physical interpretations.”

So, I ask, where do you start? What’s the first step in the process to illustrating the final painting?

Donato uses his painting of The Hobbit as an example. “I wanted all the dwarves, Gandalf, and Bilbo together, so it’s got to be before Gandalf leaves them in Mirkwood, or after he returns to the Lonely Mountains to negotiate the peace before the eagles and the orcs come. It’s a narrow window of time, so I backed it up before Mirkwood.

Donato uses his painting of The Hobbit as an example. “I wanted all the dwarves, Gandalf, and Bilbo together, so it’s got to be before Gandalf leaves them in Mirkwood, or after he returns to the Lonely Mountains to negotiate the peace before the eagles and the orcs come. It’s a narrow window of time, so I backed it up before Mirkwood.

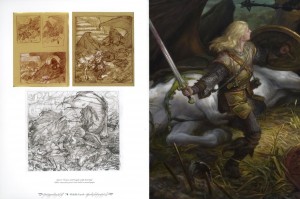

“I start scribbling these small, simple abstract shapes and designs with dynamic movement to hold the power of the composition graphically, even before any detail is considered. I play with these thumbnails, an inch or two wide, until something clicks that marries the abstract with the idea of the ‘freeze frame’ I’m after to convey the human nature or human moment I’m trying to tackle. It starts things gelling. “My thumbnail is the graphic foundation of expression to the work and upon which I build the strong emotional narrative.

“Still working intuitively, I’ll take the abstract and create a larger drawing with more detail, solidifying how many figures are in the composition and what kind of viewpoint I’m looking at for these characters.

At this stage, I get approval from an art director or client. Then I’ll start the serious aspect of gathering references, hiring models, researching environments, and considering who is going to portray the characters, like casting a movie.

“I’ve got to costume it, choreograph it, and set design it, just like a movie. That’s how I see it. So I bring all these things together, and take photographs of the models and consider the lighting.

“Up until that point, the image is vibrating in my mind, each object and aspect in a blurred compositional dance. But when something clicks and coalesces, it becomes a statue, a fixed element. Then another one comes in, balancing and complementing it, much like a puzzle coming together.

“All this information coalesces as my preliminary drawing, a large, detailed cartoon of what’s going to happen in the final painting. At that point, I am not thinking as I draw–I just do what my hand needs to.”

Donato then renders the final work in oil.

Master or student?

At forty-three, Donato has made his living as a full-time artist for seventeen years. The extensive body of his artistic work, many for name-brand corporate clients, are a testament to his talent. In addition, his numerous awards–among them three Hugos, 18 Chesleys, silver and gold medals from Spectrum, and the Hamilton King Award from the Society of Illustrators–attest to that talent and dedication. Writing in the introduction to Donato’s book, Tolkien artist Ted Nasmith wrote: “Ever since he began creating his legacy, he has been raising the art of illustration to heights it rarely achieves in our hasty, disposable modern world.”

At forty-three, Donato has made his living as a full-time artist for seventeen years. The extensive body of his artistic work, many for name-brand corporate clients, are a testament to his talent. In addition, his numerous awards–among them three Hugos, 18 Chesleys, silver and gold medals from Spectrum, and the Hamilton King Award from the Society of Illustrators–attest to that talent and dedication. Writing in the introduction to Donato’s book, Tolkien artist Ted Nasmith wrote: “Ever since he began creating his legacy, he has been raising the art of illustration to heights it rarely achieves in our hasty, disposable modern world.”

Self-deprecating by nature, Donato considers himself very much a student in its best sense: he seeks continual self-improvement as an oil painter, always wanting to reach new artistic heights. “When people ask me, ‘Why don’t you do watercolor or acrylics?’ I answer, ‘I’m still learning how to work in oil. I’m still struggling to learn how to draw, which is difficult enough.”

“With Donato,” writes Ted Nasmith, “you have a man who makes it his business to be accomplished in drapery and costume, otherworldly and terrestrial architecture in abundance, full command of perspective, landscape, macro and micro forms, dynamic composition, extraordinarily mature colour skill, inventiveness, and all with superb attention to detail and tonal dynamics.”

After singing Donato’s praises, Nasmith concludes his piece by simply stating, “Long may he delight us.”

As one of his many admirers, personally and professionally, I feel that Donato most surely will continue to amaze and delight us with his artistic imaginings for many, many years to come.

[Pick up a copy of Middle Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth]

Donato Giancola’s paintings are featured in TheOneRing.net’s Hobbit Section.

Copyright 2011 by George Beahm and Donato Giancola. Reprinted by TheOneRing.net with permission.