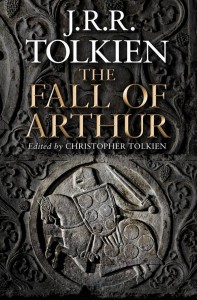

As you’re probably aware, Harper Collins is publishing J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fall of Arthur in May 2013.

As you’re probably aware, Harper Collins is publishing J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fall of Arthur in May 2013.

Edited by the Professor’s son, Christopher, the publication also includes “three illuminating essays that explore the literary world of King Arthur, reveal the deeper meaning of the verses and the painstaking work that his father applied to bring it to a finished form, and the intriguing links between The Fall of Arthur and his greatest creation, Middle-earth.”

But while we all wait, I thought people might enjoy this interesting speculation about what The Fall of Arthur might hold for us that I stumbled across over on Tolkien Library.

THE EXISTENCE of The Fall of Arthur has been known since the publication of Humphrey Carpenter’s biography of JRR Tolkien. Carpenter devoted a paragraph to the work, and uniquely, he actually quoted from it – five-and-a-half lines of alliterative verse. Given the level of interest in The Silmarillion when Carpenter was writing, and the total concentration on the canonical ‘Middle-earth’ works in the published Letters, to have that much information about anything else in the biography surely indicates that it was of importance to JRR Tolkien himself. It’s well worth quoting here what Carpenter had to say about The Fall of Arthur:

‘Another major poem from this period has alliteration but no rhyme. This is ‘The Fall of Arthur’, Tolkien’s only imaginative incursion into the Arthurian cycle, whose legends had pleased him since childhood, but which he found ‘too lavish, and fantastical, incoherent and repetitive’.

Arthurian stories were also unsatisfactory to him as myth in that they explicitly contained the Christian religion. In his own Arthurian poem he did not touch on the Grail but began an individual rendering of the Morte d’Arthur, in which the king and Gawain go to war in ‘Saxon lands’ but are summoned home by news of Mordred’s treachery.

The poem was never finished, but it was read and approved by E.V. Gordon, and by R.W. Chambers, Professor of English at London University, who considered it to be ‘great stuff – really heroic, quite apart from its value as showing how the Beowulf metre can be used in modern English’. It is also interesting in that it is one of the few pieces of writing in which Tolkien deals explicitly with sexual passion, describing Mordred’s unsated lust for Guinever (which is how Tolkien chooses to spell her name):

His bed was barren; there black phantoms

of desire unsated and savage fury

in his brain had brooded till bleak morning

But Tolkien’s Guinever is not the tragic heroine beloved by most Arthurian writers; instead she is described as

lady ruthless

fair as fay-woman and fell-minded

in the world walking for the woe of men.