British artist John Cockshaw creates the most amazing artwork of the landscapes of Middle-earth using his imagination, and a love of landscapes and macro photography. TheOneRing.net spoke with John about the techniques and inspiration behind his moody and evocative pieces in this extended interview.

British artist John Cockshaw creates the most amazing artwork of the landscapes of Middle-earth using his imagination, and a love of landscapes and macro photography. TheOneRing.net spoke with John about the techniques and inspiration behind his moody and evocative pieces in this extended interview.

Tell us a bit about yourself. The cliff notes version, I guess.

I graduated with a BA(Hons) in Fine Art from Sheffield Hallam University in 2002 followed by an MA in 2003. My art training was a real highlight of my late teens and early twenties and a natural continuation from a childhood spent drawing, painting and making miniature model sci-fi films sets in the attic for my home movies. I have always loved different styles of illustration and sci-fi and fantasy art, and as an art student this was combined with a love of Salvador Dali and his striking surreal dreamscapes. As a movie fan I was drawn to pre-production concept art and miniature-scale design work that was prevalent before the advent of CGI. I found all these influences converged in one way or another during my art training along with a further immersion in contemporary art. Then something happened that I did not expect; the release of The Fellowship of the Ring…

How long have you been working as an artist, and when you began what did you want to accomplish?

I’ve been active as an artist for almost a decade now with many projects undertaken in education, theatre design work, artist-in-residence roles in schools and small-scale film projects. I’ve been exhibiting regularly as a landscape and abstract painter since 2007 in my home county of Yorkshire. What I’ve always wanted to accomplish is an art with a mysterious and intriguing pull on the viewer, providing suggestive hints of a wider narrative or mood – a little invitation for the viewer’s imagination to enter the work. This element has really come to the forefront in the collection of Tolkien inspired work. With From Mordor to the Misty Mountains I hope to begin establishing a reputation as a distinctive UK Tolkien artist, joining the ranks of others internationally who are inspired and compelled to create art in the same vein.

How did you become interested in Tolkien and Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit? What drew you to them and what do you like about them?

How did you become interested in Tolkien and Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit? What drew you to them and what do you like about them?

Going back to the release of Fellowship in 2001 it was Peter Jackson’s films that were the first entry point into Tolkien for me. Between 2002 and 2003 when The Two Towers was fresh in the mind from its theatrical release, I remember having a growing interest to respond to the world of Middle-earth artistically. A large appeal lay in the epic scope of the art direction, cinematography and the miniature-scale work of the fantasy locations. This prompted me to dig into Tolkien’s mythology deeper by devouring the books and I simultaneously began to hold Howard Shore’s magnificent film scores in high regard. Its beauty aside, Shore’s score is incredibly effective in helping you ‘see’ Middle-earth through its undulating and towering orchestral landscape. The music is now a central inspiration and I’ve been following Doug Adams’ analysis of it for well over six years, through his blog and 2010 book. I also became hooked on the BBC Radio dramatisation of The Lord of the Rings from the 1980s (the one with Ian Holm playing the role of Frodo) which tided me over until The Return of the King in 2003, and I still return to it again and again – it’s a good companion piece to both the experience of the films and reading Tolkien’s writing. The main draw for me, which feeds into the work I create, is the richly described character and believability of Middle-earth – a fantasy land rooted in the real world, epic in scale but familiar enough to see echoes of it all around you, very much like the genius move to take New Zealand and just by careful additions and manipulation transform it into a living, breathing fantasy land.

What was the moment when you decided you wanted to apply your artistic talent to creating Lord of the Rings artworks? Was there a particular trigger?

Funnily enough I don’t think I decided it just happened naturally, with a strong trigger right at the end. The inspiration I had to create work in response Middle-earth needed bedding in and a long period of gestation until a firm notion appeared about what form it should take. Rushing wasn’t an option. Like many fans of J.R.R Tolkien’s work I carried my appreciation of that mythology everywhere with me and particularly on long walks over the English countryside, when striding over the moorland in a bracing five-beat Isengard pattern (a reference for Shore enthusiasts there). It was when I began to see Tolkien-esque familiarities in landscapes and architectural features all around me that I kept returning to the idea of forming a fantasy land from real world elements. The Middle-earth of the movies was so effective because of the feeling that you knew it, that it could be somewhere you’d perhaps visited or where you lived yourself. Lucky enough to live in a quaint and historical part of the North of England surrounded by landscape of great character both near and far I had a rich source of inspiration to draw from. My local city of Ripon can often feel like a pleasant stroll through Bree at times. The trigger came from Alan Lee and John Howe’s paintings, and like the filmmakers who were similarly inspired, I was captivated by their hauntingly beautiful watercolour illustrations. I loved the atmospheric details of climate in their depictions of Middle-earth as well as the fact that Middle-earth stood foremost as a central character integral to the illustrated scene.

What is it that you try to achieve when you develop a piece?

What is it that you try to achieve when you develop a piece?

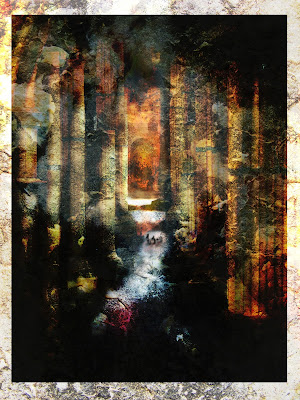

My plan for From Mordor to the Misty Mountains (an unintentional homage to John Howe’s categories of his Lord of the Rings artwork on his website) was that it was going to look illustrative and have a cinematic quality, but any action and character content was going to happen on the periphery of the scene or out of shot to allow the features of the Middle-earth landscape to come to the fore, work their magic and stir the imagination. Any references to characters would mostly be small and distant. In the same immersive way you might engage with a given landscape when going on a long distance walk, say, the aim was to really draw viewers in establish a strong sense of viewpoint: that of a Middle-earth journeyman or wandering hobbit traversing the landscape on foot.

Tell us about the first LOTR-inspired artwork you did, what made you choose that one, and what you think of it now.

The first work in the collection that I completed was Campfire at the Watchtower of Amon Sul and it became the test case. The approach to the work was straightforward at this stage in particular with this piece; take a great photograph of a rugged Scottish landscape and tweak it ever so slightly to look like a scene from The Lord of the Rings without looking artificial. It became apparent quite quickly that I had managed to achieve the result I’d been after and it possessed the qualities I’d set out to capture. I look back at it now and I still like it greatly. It serves to illustrate how the work has taken on two styles that sit well side by side: the tendency towards the cinematic and photo-real and the much more illustrative.

How long do these pieces generally take to create?

These pieces can vary quite considerably. Some may be done over two to three nights (always a gap to allow for evaluation and improvement) but some pieces might take blood, sweat and tears over a number of weeks to complete. The Shire is a case in point, the basic composition of the image was locked quickly in a flash of inspiration but it took weeks of redrafting and altering before it really came to be finished. I won’t venture into technical details, but will just say that the lighting wasn’t right and tree-lines weren’t right. It took a lot to get the right degree of Middle-earth into that composition. But eventually hard work rewards you…if you’re lucky.

Can you just generally map out the creative process and the planning involved, from concept to finished work, for us?

Can you just generally map out the creative process and the planning involved, from concept to finished work, for us?

Taking an ever-expanding library of my photography which has grown and been carefully edited down to a best selection over seven years. A composition will typically be assembled digitally from two to three initial photographic elements that are enhanced by progressive layers of colour and photographic elements. At an earlier point in the planning stage each digital composition had a sketched-out equivalent in photographic terms – essentially a physically cut and pasted photo collage. That sketchbook-like process has been eliminated now that I’m a bit more adept at digital work, but in the beginning my working practice and approach was very much from the vantage point of an oil painter. I’m trying not to be too technical in my description of the process as it can be more interesting to retain some of the mystery and for artists in general to keep a degree of their working practice elusive.

What sort of equipment do you use?

In terms of equipment I use a Fujifilm Finepix S5800 which gets me the results I need and is nicely portable and has joined me in many a scramble up rocky hills and squeezing into confined cliff crevices to get the shots I’ve needed. It was passed on to me by my brother James and I’m a sentimental fellow who will love it until it works no more. It’s a great means to an end of getting the perfectly composed photograph to be worked into the final composition. It’s also up to the job of getting the quickly discovered shot, the instant image of an opportune encounter with landscape that, like a quick sketch, will inform the larger whole. The digital processing is completed using Gimp, the open source image manipulation software.

You say you work on a micro, macro and landscape scale. For people who aren’t necessarily familiar with photography, can you explain what this means, and how these elements come together to create the finished work?

Put simply the work is composed from an exhaustive range of landscape views photographed on my travels in the UK but also from my expeditions abroad such as Austria and Tunisia for example. But working in effective combination with this are photographs of micro-landscapes that are discovered when you really scrutinise the landscape close-up. So this is where you get extremely close to a subject and photograph that section of tree bark that, via the Macro lens, becomes a mountain ridge or the minute sections of driftwood found on a beach that become the looming tower of Cirith Ungol or the forbidding Minas Morgul. This is where my love of the miniature-scale work employed for The Lord of the Rings comes in. Combining these full-size and miniature scale elements is really just a case of creative composition and careful selection, but I learnt from studying the special effects documentaries for the trilogy just how clever miniature work can be and it provides a great joy when the effect can be pulled off quite creatively. The Hobbit will no longer utilise miniature work on account of the advances in technology, but I have no doubt the quality of the CGI will look as delicately crafted, intricate and continue to hold the same breathtaking appeal.

I’m curious about your scouting of places and locations, as it seems as though it could be a kind of homage to parts of the English countryside you like? Is it a process of random discovery, or do you have some plan?

I’m curious about your scouting of places and locations, as it seems as though it could be a kind of homage to parts of the English countryside you like? Is it a process of random discovery, or do you have some plan?

The scouting of the places and locations is nothing but a sheer joy of the project. It often isn’t planned but I try and make use of every location that I newly visit or return to again and again. There is a certain degree of homage to the English countryside I like mirroring Tolkien’s love of his home country, but to be honest my hawk-like eyes could find Middle-earth wherever I found myself. Mostly it is a random discovery of places which makes it fun to be constantly on the look-out for opportunities, but on the few occasions I haven’t had my camera with me it’s been a real wrench and I’ve learnt from that mistake! Another element of location scouting is that when you’re scrutinising a landscape close-up on a miniature scale you’ve just made your world twice as vast for photographic opportunities. My poor wife has suffered on many lovely walks where I’ve stopped for an impromptu but extensive photo-shoot!

I’d love if you could briefly profile for us a couple of your Middle-earth creations.

Starting with Minas Tirith I had great elements for the foreground and background sections of the composition from photographs taken in Snowdonia National Park, North Wales and Mountain peaks taken near the Italian border of Austria. The problem was coming up with a convincing method of creating a hint of the regal majesty of Minas Tirith that could sit centrally in the landscape. The result I arrived at involved composing a likeness of the city using photo elements of sheer white cliff faces taken in Cornwall in the South West of England. The White Tower of Ecthelion was an industrial tower that I’d spotted and photographed 5 years previously whilst on a 12-mile walk in South Yorkshire. All of a sudden Minas Tirith nestled discreetly in the hills of the composition with only atmospheric details of mist, a subtly lit beacon and added texture to bring it to life.

With Fangorn Forest (Beneath the roof of sleeping leaves the dreams of trees unfold) I built up a likeness of Treebeard’s tall frame and limb branches from an extensive scouting of tree elements that possessed a figurative likeness. The facial composition of Treebeard was much harder to get right but I’d had no problem with finding facial likenesses in bark texture etc. As a test I made a physical photo collage which worked very well, however the digital equivalent very quickly fell apart. So to complete the full figure I combined the digital figure with a digital scan of the collaged face and with further blending gave it a more accurate appearance. One afternoon in my local woodland I spied a section of trees that I immediately knew was a perfect spot for Treebeard to occupy. With further lighting adjustments and atmospheric details the composition was complete.

With Fangorn Forest (Beneath the roof of sleeping leaves the dreams of trees unfold) I built up a likeness of Treebeard’s tall frame and limb branches from an extensive scouting of tree elements that possessed a figurative likeness. The facial composition of Treebeard was much harder to get right but I’d had no problem with finding facial likenesses in bark texture etc. As a test I made a physical photo collage which worked very well, however the digital equivalent very quickly fell apart. So to complete the full figure I combined the digital figure with a digital scan of the collaged face and with further blending gave it a more accurate appearance. One afternoon in my local woodland I spied a section of trees that I immediately knew was a perfect spot for Treebeard to occupy. With further lighting adjustments and atmospheric details the composition was complete.

Have you submitted your art to competitions? I understand you’re exhibiting right now?

I’m very excited about current and future interest in the collection of artwork. Many viewers have found certain Boschian and Pre-Raphaelite similarities in specific pieces, which is fascinating and part of the whole beauty of opening the work up to interpretation. First and foremost the work will be available for purchase at The Rapture Gallery in Harrogate within my locality of North Yorkshire. What first inspired me to approach the gallery for this collection was the owner and Artist/Sculptor Wayne Malton’s amazing Balrog sculpture that he had just completed as a commission. I knew this would be a good home for the work. It is hoped other venues will express interest as exposure builds and I’m hoping something will be take place within my home city of Ripon. I’ve recently been interviewed by UK fan site The Hobbit Movie and had a selection of the work featured on the site. I’m in the process of arranging a project for Spring 2013 with Sarehole Mill in Birmingham, a location with a strong connection to Tolkien’s childhood that is interested in hosting the work in a yet to be decided manner. Sarehole Mill is a romantic site and a fully working mill but because of its size the project will be will ultimately be on a small scale, but whether it’s an eventual display or interior / exterior installation it will be a huge privilege to be involved with a location that has a strong link to Tolkien’s past. Details are to be confirmed.

What would you like to do next? Do you have any more LoTR projects in the fire?

What would you like to do next? Do you have any more LoTR projects in the fire?

I’m going to continue with the collection and further refine my techniques. I intend to begin working on pieces in direct response to The Hobbit films, but an element of just enjoying and living with the films for a bit and appreciating Howard Shore’s score as well will be required. I hope to carry on building my reputation as a distinctive UK Tolkien artist by continued exposure of the work.

In terms of other Lord of the Rings projects in the fire, well there is a little oddity that I’d like to mention that I completed earlier this year. With dogged determination and a passion that never burned out I completed a short zero-budget film, a two-parter of 15 minutes apiece, where elements of sci-fi cinema merged with art house and fantasy. The film mirrors certain aspects of Chris Marker’s La Jetee and story-wise concerns a variation on the Ring of Power idea. Completing it was a fight against constant equipment failure and other difficulties but it was a sheer labour of love and a trailer is available to view on the blog I’m just not too sure how well the name translates as it’s called The Power of Ultram which I think in the US is a brand name for the drug Tramadol.

Thank you greatly, it’s been a pleasure to spend time with TheOneRing.net and share my work with its community of fans.

Readers can visit John’s site here to find out more about his works, his ideas and his exhibits. TORn is also hosting a more extensive gallery of images here.