The Tolkien Society got me thinking. This year’s Tolkien Reading Day had a nautical theme – some breezy thing about International Seafarer Day. Why? Is Tolkien a particularly “nautical” writer? I admit this had never occurred to me. From the very idea of Middle-earth, a land before time that approximates continental Europe with land bridges to England and Africa; to the endless series of quests across mountains, forests, fields and caverns that Tolkien loves to describe in breathtaking language; to the most famous fantasy race of Halflings that ever turned pale at the thought of crossing open water, Tolkien has always seemed to me to have his literary feet planted firmly in dry land, like the roots of his beloved trees.

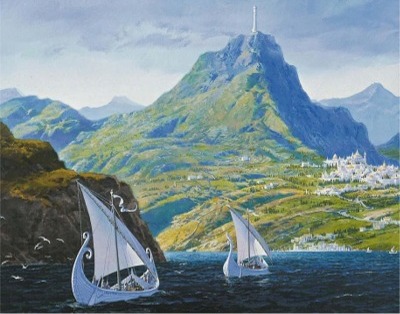

Not that he doesn’t treat with the Sea. Of course he does. Every foreground needs its background. Who doesn’t know that the great Western or Sundering Sea is the barrier between the mortal Great Lands (Tolkien’s original name for Middle-earth’s central continent) and the Undying Lands of Elvenhome and Valinor? Only the Elves may cross this Sea – with the usual exceptions of various mortal Heroes taking their numbers and awaiting their chances. The Elves have the Sea-longing embedded in them. Legolas is warned by Galadriel that once he hears the seagulls at Pelargir in southern Gondor, he will never again be at rest in his woodland home. Ted Sandyman mocks Sam’s love of the tale of the Elves: “sailing, sailing, into the West” – a theme echoed by Saruman at the end of the story as he taunts Galadriel for her exile on the wrong side of the great water.

But this is symbolism. Elvenhome was originally England, in Tolkien’s youthful conception. England is an island at the edge of the Atlantic, and it was a great seafaring Empire at that time. Tolkien, in his desire to create the apocryphal “mythology for England”, could not ignore the Sea, both inner and outer, in his Elvish pre-history of the Sceptred Isle. The concept of a great Sea supporting a blessed island, far to the West of the Continent, survived the death of his early dream. It lived on in the purely Elvish chronicles of The Silmarillion, and eventually The Lord of the Rings.

It is always there, but we never actually sail that symbolic Sea. We hear about innumerable voyages, epics of nautical derring-do by the Noldorin Elves, the Teleri Sea-Elves, Feanor, Earendil, Tuor, Eldarion prince of Numenor, Ar-Pharazon the Great, Elendil the Tall and his sons, Amroth, Cirdan the Shipwright, and the Ship-Kings of Gondor. These voyages always take place off-stage. In none of these tales do we taste the salt on our lips or feel the wind in our hair. In Tolkien’s world, these intrepid mariners leave the Land only to reach another Land or return to their own Land in defeat. In the annals of Middle-earth there is no action at sea, no description of the moods of the ocean, no engagement with the voyages as voyages. Tolkien’s Sea for all its greatness is merely the context for a text about Lands. Occasionally it dresses in another robe, such as in the Númenórean tale of The Mariner’s Wife, where the Sea becomes a metaphor for the undomesticated Male spirit; or in the person of Ulmo, the Vala of the Sea in The Silmarillion who turns the sound of storm-tossed waves into a horn-call of deepest wisdom and reassurance for the isolated humans and Elves stranded in Middle-earth.

Yet English literature is rich with sea-stories, as one might expect of the Empire on which the sun never set. I recall reading, in the same years I discovered Tolkien and from the same Anglophilic mid-century library: the epic Bounty trilogy by Nordhoff and Hall; the classic Hornblower series by Forester; Endurance by Lansing on Shackleton’s incredible seamanship; Gipsy Moth Circles the World by Sir Francis Chichester; the Rime of the Ancient Mariner; and even frequent seafaring adventures in the books of Nevil Shute, who is generally thought of as an aviation novelist. These books, whether fiction or non-fiction, grip you with their eloquent and detailed descriptions of Man against the Sea: page after page of well-crafted prose about storms, waves, cold salt water, tackle and rigging, starvation and thirst, sunsets, the infinite stars at night, sea monsters, loneliness and companionship in the greatest deserts on earth, and the relief and shock of the return to terra firma.

Why did the very English Tolkien never really write about adventures at sea? I don’t think it’s profitable to try to prove a negative, so I will just speculate. Leave aside mundane ideas like the fact that Tolkien never sailed off his island, but loved to hike the English countryside. It seems to me that Tolkien’s biggest themes are variations on Man’s struggle with himself: intensely moral struggles such as mortality vs. immortality, good vs. evil, heroism vs. prudence, faith vs. reason, and myth vs. history, to name a few. In the Medieval and Victorian sources that Tolkien knew and liked the most, and from which he drew his romances, these struggles are traditionally externalized as stories of law-breaking or quests or wars. What has gone without saying is that they also take place in land-bound settings.

Sea stories, on the other hand, are about Man’s struggle with the sea – a sea which is an amoral force of nature. There is no inner struggle for a sailor, just an outer struggle for survival. Triumph over the sea is possible, but temporary, and conveys no special grace on the victor – the next voyage or the next wave could still be the last one. From this point of view, a sea voyage is no subject for a writer whose secondary world fairly breathes an innate morality.

As I think about it, I remember that Tolkien stumbled over this prime characteristic of the sea in his creation of Ulmo. In The Silmarillion Ulmo, the Vala (god) of the sea, is the only great spirit who is unreservedly on the side of the Elves (and later the Men), when the rest of Valinor turns away from the war with Morgoth over the Silmarils. Yet a beneficent Sea is a real corker in mythology, literature, and reality too – so Tolkien invented Ossë, a Maia (lesser spirit) of the coastal waters who is a bit crazy. Ossë and his spouse Uinen, Lady of the sea plants and creatures, are the ones who dominate the sea lanes most often used by the fishing and trading ships of the Elves and Men in Tolkien’s stories. Thanks to Osse’s love of violence “at times he will rage in his willfulness without any command from Ulmo” (Sil 30). Ah… blame storms and shipwrecks on the henchman, not the boss. And said boss Ulmo – god of the Sea – is thus left free to concern himself almost entirely with events on the Land!

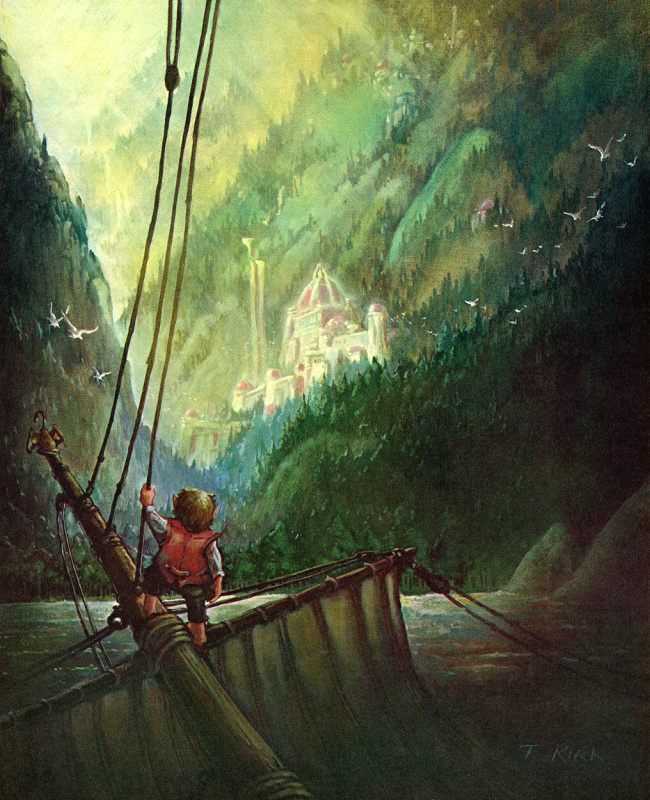

With such a complex mythological construction to moralize the essential amorality of the Sea, it’s no wonder that Tolkien never embarked on writing up the breezy details of any of his heroes’ ocean voyages – even in his unfinished tales of Númenor, as surefire a nautical setting as any writer could wish for. It’s a pity, since he wrote so well about outdoor adventures in natural landscapes. Imagine a rip-roaring tale of the sea by Tolkien, who so lightly showed us what he could do with lesser voyages by lesser craft:

…the boats whirled by, frail and fleeting as little leaves… the black waters roared and echoed, and a wind screamed over them. ‘Fear not!’ said a strange voice behind him. In the stern sat Aragorn son of Arathorn, proud and erect, guiding the boat with skilful strokes; his hood was cast back, and his dark hair was blowing in the wind, a light was in his eyes… (LotR II.10)